All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know AML.

The aml Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the aml Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The aml and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The AML Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Syndax, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kura Oncology, AbbVie, and has been supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group.

Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View AML content recommended for you

Maintenance therapy in AML: Treatment options and clinical considerations

Do you know... Which of the following is an approved oral maintenance treatment for older patients with AML in remission after intensive chemotherapy and not proceeding to HSCT?

Recent developments in therapeutics and supportive care have led to improved outcomes for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1,2 However, despite the attainment of initial complete remission (CR), i.e., a measurable residual disease (MRD)-negative state, following standard induction and consolidation therapy, relapse remains the primary challenge in achieving long-term survival for patients with AML.3 Maintenance therapy, a less intensive and extended treatment following the initial intensive induction–consolidation chemotherapy, can be a viable treatment option to prevent relapse and prolong survival.1

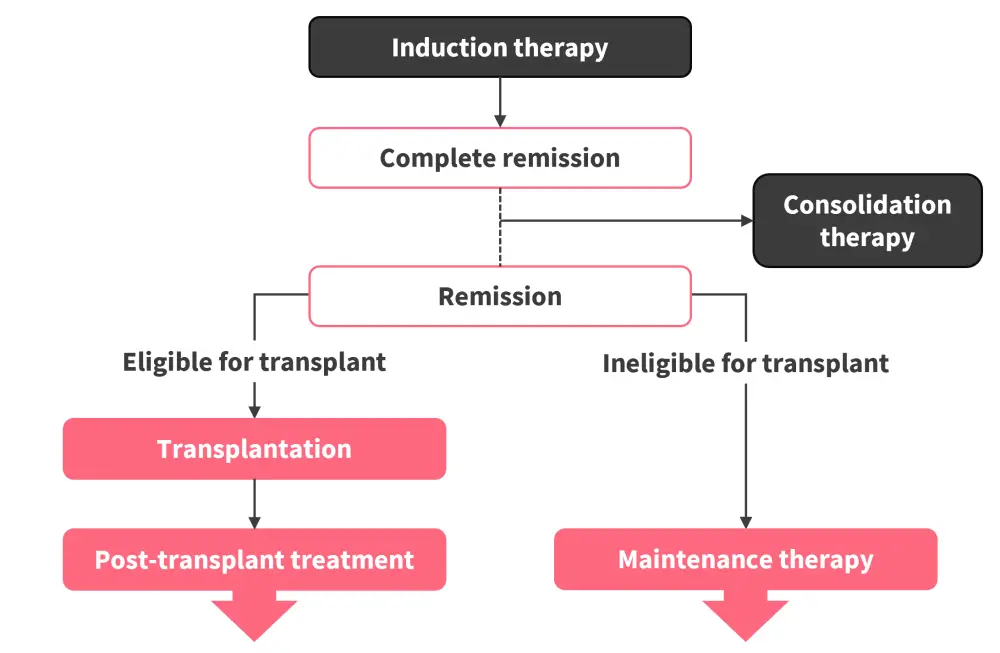

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines maintenance therapy for AML as “an extended but time-limited course of treatment, usually relatively nontoxic, given after achievement of CR with the objective of reducing the risk of relapse beyond the period of treatment.”4,5 Figure 1 presents a schema of treatment pathways to maintain remission in AML.

Figure 1. Post-remission treatment strategies in AML*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

*Data from Senapati et al.1

Given the biological diversity of AML, maintenance therapy should be considered based on a patient’s genomic profile, 2022 European LeukemiaNet ( ELN) risk stratification, remission status, and eligibility for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT).1 Notably, assessment of MRD is also crucial for identifying patients at high risk of relapse and those who may benefit from maintenance treatment.6 One of the objectives of maintenance therapy is to eradicate MRD in patients with MRD-positive remission or to convert them from a MRD-positive to -negative state, 1,6 with the overarching goal to enable patients with AML in remission to attain a normal quality of life while extending remission duration and overall survival (OS).1 Below we discuss maintenance treatment options in AML and their key clinical considerations.

Maintenance therapies

Cytotoxic chemotherapy

Early maintenance strategies after consolidation in patients with AML who were ineligible for allo-HSCT involved the continued use of cytotoxic chemotherapy.2 However, due to a lack of survival benefits, chemotherapy-based maintenance approaches are not routinely practiced in AML.1

Epigenetic modifiers: Hypomethylating agents

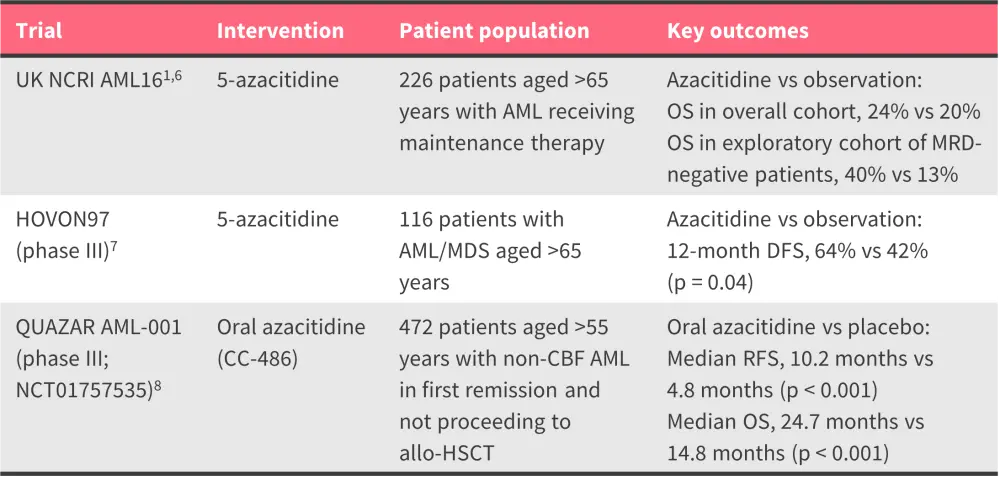

Various hypomethylating agents (HMAs), particularly azacitidine, have been investigated in clinical trials for use as maintenance therapy in patients with AML in remission (Tables 1 and 2). Maintenance therapy with subcutaneous 5-azacitidine in older patients with AML in remission showed improved disease-free survival but no significant OS advantage in the phase III HOVON97 trial.7 However, the UK NCRI trial reported that patients with MRD negativity who received azacitidine as maintenance therapy had improved outcomes compared with the observation group.2,6

One of the most significant advancements in maintenance strategies for AML was the development of an oral formulation of azacitidine (CC-486). In the phase III QUAZAR AML-001 trial (NCT01757535), oral azacitidine administered over 14 days in 28-day cycles as continuous postremission therapy was associated with significantly longer OS and relapse-free survival (RFS) compared with placebo among older patients (aged ≥55 years) with AML who were in CR after chemotherapy.8 Based on results from the QUAZAR AML-001 trial, oral azacitidine monotherapy has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Commission (EC) as a maintenance therapy in older patients with AML in first CR/CR with incomplete blood count recovery following intensive chemotherapy and not proceeding to allo-HSCT.9,10

Multivariate analyses from the QUAZAR-AML trial showed that oral azacitidine significantly prolonged OS and RFS independently of baseline MRD status, and rate of transition from MRD positivity at baseline to MRD negativity during treatment was higher with oral azacitidine (37%) vs placebo (19%).11 Post hoc subgroup analyses revealed that oral azacitidine maintenance therapy improved RFS compared with placebo across most mutational subgroups detected at baseline, particularly in patients with leukemic DNMT3A and SRSF2 mutations.12 Additionally, exploratory analysis showed that patients’ health-related quality of life was preserved with oral azacitidine, with European Quality of Life-5 Dimension-3 Levels (EQ-5D-3L) and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-fatigue scores remaining at or above baseline levels at almost all evaluation timepoints.8 However, it should be noted that the QUAZAR AML-001 trial did not include patients younger than 55 years nor those with core binding factor (CBF) AML, and only 14% of patients had adverse-risk cytogenetics, which limits the generalizability of the findings.4

Table 1. Key completed trials of HMAs in the maintenance setting for AML*

allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; HMA, hypomethylating agent; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; OS, overall survival; MRD, minimal residual disease; RFS, relapse-free survival.

*Data from Senapati et al.1, Molica et al.6, Huls et al.7, and Wei et al.8

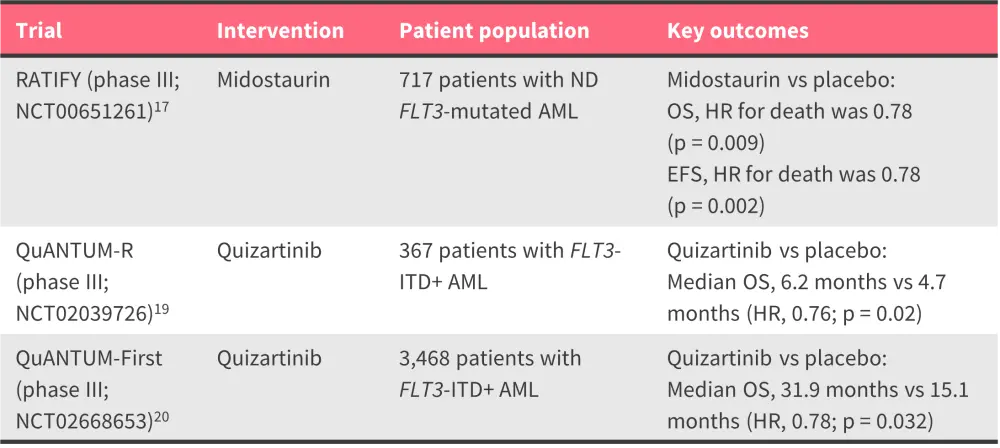

Table 2. Key ongoing trials of HMAs in the maintenance setting for AML*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; HMA, hypomethylating agent.

*Data from ClinicalTrials.gov.13,14

Question 1 / 2

In the QUAZAR AML-001 trial, what was the median overall survival of patients with AML receiving oral azacitidine maintenance therapy?

A

15.6 months

B

24.7 months

C

30.0 months

D

12.5 months

Given the convenience of its oral formulation, the possibility of at-home administration, and its approval status, oral azacitidine is being widely used in clinics for treating older patients in remission who are not eligible for allo-HSCT or choose not to undergo allo-HSCT due to personal preferences. An overview of real-world studies on oral azacitidine can be found here.

To gain deeper insights into the use of oral azacitidine, explore our expert interviews with:

- Andrew Wei, discussing QUAZAR: Should maintenance with CC-486 become standard of care following induction chemotherapy?

- Cristina Papayannidis, discussing How I treat a patient with DNMT3A-mutated AML in remission post intensive chemotherapy

In patients with CBF-AML who are unable to complete designated cycles of fludarabine, cytarabine, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and gemtuzumab ozogamicin intensive induction chemotherapy regimens, or have persistent MRD positivity after consolidation therapy, decitabine maintenance treatment is an option.1 This is based on a single arm study of 31 patients with CBF-AML treated with fludarabine-high-dose cytarabine-based intensive induction therapy. In 23 patients with persistent MRD positivity, maintenance with decitabine resulted in 52% CR with a median molecular RFS of 93 months.1 Further studies of MRD-based HMA maintenance are needed.

Targeted therapies

FLT3 inhibitors

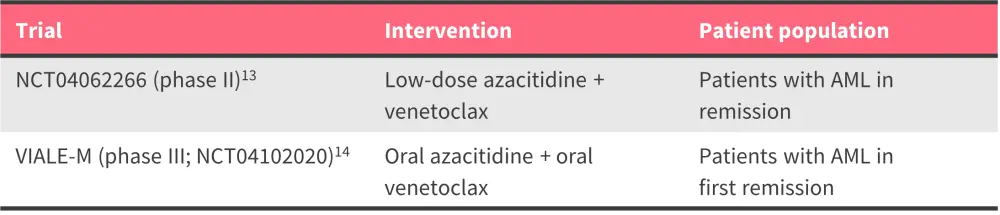

The addition of quizartinib to intensive chemotherapy followed by maintenance therapy improved RFS and OS in patients with FLT3-ITD AML in the phase III QuANTUM-First trial (NCT02668653). Subsequently, quizartinib received approval from the FDA15 and the EC16 as maintenance monotherapy following consolidation chemotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with newly diagnosed FLT3-ITD+ AML.

Watch our expert opinion interview with Harry Erba discussing updates from the Society of Hematologic Oncology (SOHO) 2023 Annual Meeting on the QuANTUM-First trial.

Midostaurin was assessed in the phase III RATIFY (NCT00651261) trial, where it was added to induction and consolidation therapy, then continued as maintenance for 12 months.17 Although subsequently approved by the FDA as an add-on to intensive induction and consolidation therapy in patients with FLT3-mutated AML,18 the trial was not designed to investigate the independent effect of midostaurin maintenance therapy and post hoc analysis was unable to determine any survival benefit with maintenance midostaurin.2,17 However, the 2022 ELN guidelines recommend continuation of midostaurin after consolidation if patients also received it during induction and consolidation, according to the RATIFY protocol.2,4

An overview of the key completed trials investigating FLT3 inhibitors in the maintenance setting for AML is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Key completed trials of FLT3 inhibitors as maintenance therapy in AML*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; EFS, event-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; ND, newly diagnosed; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

*Data from Stone et al.17, Cortes et al.19, and Erba et al.20

Question 1 / 1

Which of the following statements regarding midostaurin is correct?

A

It is not recommended as a maintenance therapy, regardless of induction and consolidation therapy received.

B

Although not approved by the FDA as a maintenance therapy, it is recommended after consolidation for those who received midostaurin during induction and consolidation.

C

It is approved by the FDA as a maintenance therapy in patients with FLT3-mutated AML.

D

It is approved by the FDA as an add-on to intensive induction, consolidation, and maintenance therapy in patients with FLT3-mutated AML.

Immunotherapies

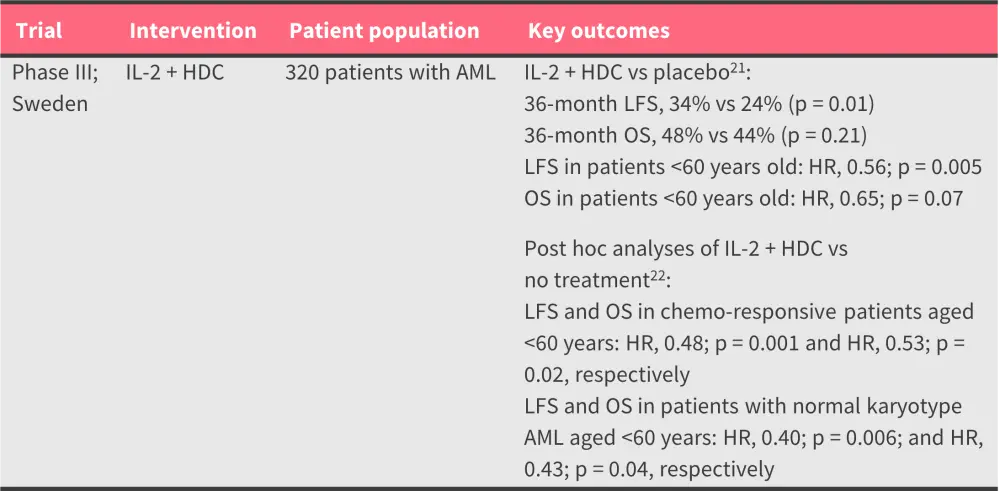

Maintenance therapy with cytokines interleukin-2 (IL-2), and interferon alpha (IFNα) have been studied in several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (Table 4).2 Despite the biologic rationale, RCTs of IFNα have failed to show a benefit for IFNα as a maintenance strategy.2

IL-2 is a widely used cytokine; however, it has shown limited clinical benefit, particularly at low doses.2 When combined with histamine dihydrochloride in a phase III Swedish trial of 320 patients with AML in CR, it showed improvement in leukemia-free survival and,2,21 although the improvements in leukemia-free survival did not translate to OS benefits, the combination was well tolerated, with 92% of non-relapsed patients completing all planned treatment cycles.2,21 Post hoc analyses found the combination effective in preventing relapse in patients with chemo-responsive AML, normal karyotype AML, and those aged 40–60 years.22 The combination of IL-2 plus histamine dihydrochloride has received approval from the EC as a maintenance treatment in adults with AML; however, its efficacy in patients aged >60 years has not been fully demonstrated.23

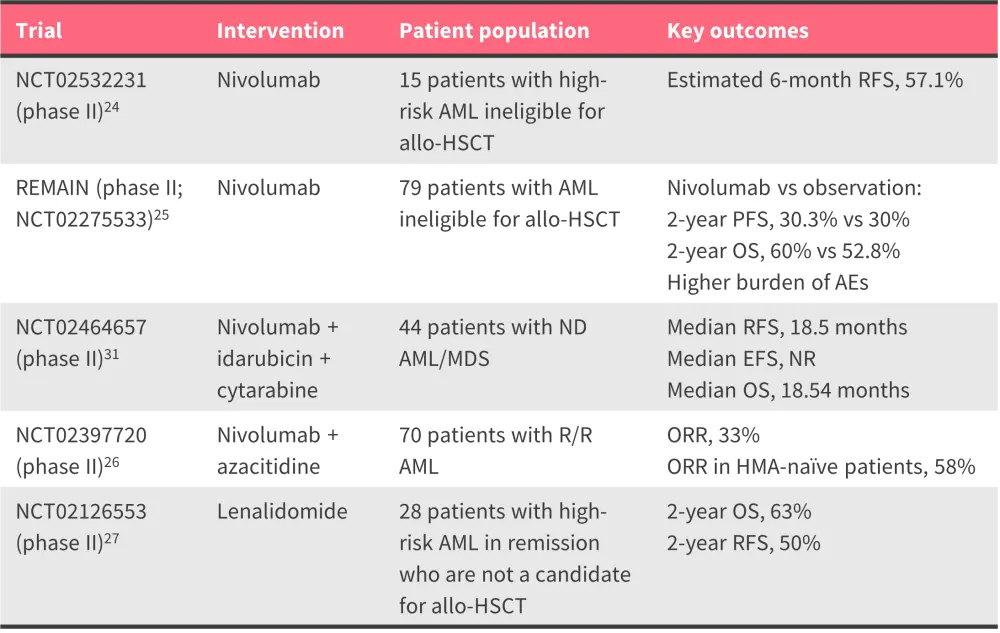

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, which block immune inhibitory molecules, have also been studied for their efficacy as maintenance therapy in AML (Table 5).2 The safety and feasibility of nivolumab maintenance therapy in patients with high-risk AML has been demonstrated; however, a phase II trial showed limited effectiveness in eradicating MRD and extending remissions.24 In addition, nivolumab failed to improve survival and had an increased incidence of adverse events in the phase II REMAIN (NCT02275533) trial in poor- and intermediate-risk patients with AML ineligible for allo-HSCT.25 When combined with azacitidine in a phase II trial, nivolumab showed promising response and survival rates, especially in HMA-naïve and Salvage 1 patients with R/R AML.26 Lenalidomide appeared to be a safe and feasible maintenance strategy in a single arm phase II trial in patients with high-risk AML who were not ineligible for HSCT.2,27 The survival benefits were more pronounced in patients with non-secondary AML and those with undetectable MRD, however larger randomized studies are warranted to confirm the benefits.2,27

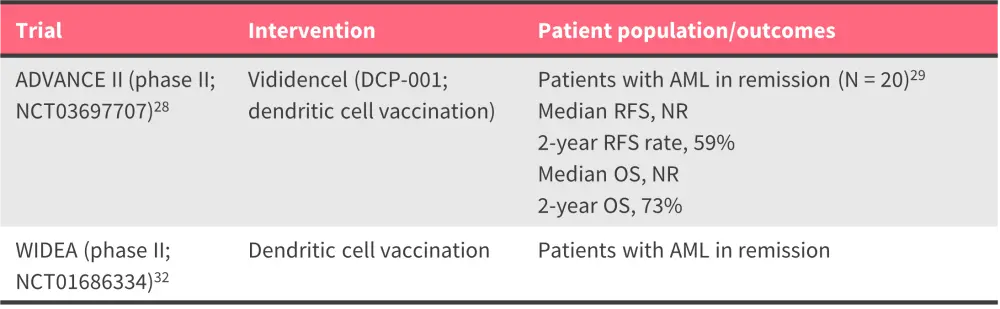

Vaccine-based approaches hold promise as maintenance therapy in AML given that the immune system of patients with AML in morphologic remission may better respond to vaccines and eradicate residual leukemia cells (Table 6).3 Vididencel (DCP-001), an off-the-shelf, allogeneic dendritic cell vaccine, is currently being investigated as monotherapy in the phase II ADVANCE II trial in patients in CR with MRD.28 Given its potential to control MRD and induce durable relapse-free survival, vididencel received fast track designation from the FDA.29 Vididencel is also being investigated in combination with oral azacitidine in the AMLM22-CADENCE trial (ACTRN12619000248167) for its ability to maintain or induce MRD negativity in patients with AML who are in first CR following intensive chemotherapy but ineligible for allo-HSCT.30

Table 4. Key completed trials of cytokine therapies as maintenance treatment for AML*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; HDC, histamine dihydrochloride; HR, hazard ratio; IL-2, interleukin-2; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival; R/R, relapsed/refractory; LFS, leukemia-free survival.

*Data from Brune et al.21 and Hellstrand et al.22

Table 5. Key completed trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors as maintenance therapy for AML*

allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; EFS, event-free survival; HDC, histamine dihydrochloride; HMA, hypomethylating agent; ND, newly diagnosed; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RFS, relapse-free survival; R/R, relapsed/refractory; LFS, leukemia-free survival.

*Data from Reville et al.24, Liu et al.25, Daver et al.26, Abou et al.27, and Ravandi et al.31

Table 6. Key ongoing trials of vaccine-based approaches as maintenance immunotherapies for AML*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival.

*Data from ClinicalTrials.gov28,32 and van de Loosdrecht.29

Question 1 / 1

Which of the following immunotherapies is approved by the European Commission as a maintenance treatment in adults with AML?

A

CTL-4 inhibitor

B

PD-1 inhibitor

C

IFN-alpha in combination with histamine dihydrochloride

D

IL2 in combination with histamine dihydrochloride

Maintenance therapy options following transplantation

Transplantation continues to be the most effective post-remission therapy in AML.2 However, the main cause of HSCT failure is post-transplant relapse, which affects ~40–70% of patients, and particularly those treated with reduced-intensity conditioning.33 In recent years, clinical trials of targeted therapies, such as FLT3 and IDH1/2 inhibitors, HMAs, and BCL2 inhibitors demonstrate potential for future use in post-transplant maintenance for AML,33 briefly described below.

Targeted therapies

FLT3 inhibitors

Several FLT3 inhibitors, such as sorafenib, gilteritinib, midostaurin, and quizartinib, have been investigated in clinical trials. Among these, sorafenib has the most robust data supporting its use as a maintenance therapy post allo-HSCT in patients with AML. In the phase II SORMAIN trial, sorafenib demonstrated a reduced risk of relapse and mortality in patients with FLT3-ITD-positive AML after allo-HSCT.1,34 Moreover, MRD-negativity pre-HCT and MRD-positivity post-HSCT were strong predictors of improved survival with sorafenib maintenance.34 Maintenance therapy with sorafenib reduced the incidence of relapse and was well tolerated in a phase III trial conducted in China,1,35 further supporting this strategy as a standard of care for patients with FLT3-ITD-positive AML undergoing allo-HSCT.35

Watch our interview with Yi-Bin Chen discussing the potential of sorafenib maintenance treatment in FLT3-mutated AML.

Midostaurin was evaluated as maintenance therapy post allo-HSCT in the phase III RADIUS (NCT01883362) trial; however, the primary endpoint of RFS was not met.36 A correlative analysis revealed that patients who could tolerate midostaurin and continued therapy, reflected by higher levels of phosphorylated FLT3 inhibition, experienced sustained benefits and improved long-term outcomes.36

The phase III MORPHO (NCT02997202) trial assessing gilteritinib in patients with FLT3-ITD-positive AML following HSCT failed to meet the primary endpoint of RFS.37 However, gilteritinib showed RFS benefit (2-year RFS, 77.2%) in ~50% of patients with FLT3-mutated AML who were MRD positive either pre- or post-allo-HSCT. The findings of this trial suggest that post-allo-HSCT gilteritinib maintenance therapy could be the standard of care for patients with FLT3-ITD AML who are MRD-positive pre- or post-allo-HSCT. Furthermore, in the long-term follow-up of the phase III ADMIRAL (NCT02421939) trial, gilteritinib maintenance treatment post-HSCT showed sustained remission and a stable safety profile.38

Watch our video interview with AML Hub Co-Chair, Charles Craddock discussing How might the MORPHO trial of gilteritinib impact clinical practice?

Quizartinib demonstrated tolerability and reduced relapse rate after allo-HSCT in patients with FLT3-ITD AML in a phase I trial.39 However, due to lack of evidence of improvement in OS and its association with risks, such as QT prolongation, torsades de pointes,40 and cardiac arrest, it is not currently indicated as maintenance monotherapy post-allo-HSCT.15

Question 1 / 1

Findings from the phase III MORPHO trial suggest that post-allo-HSCT gilteritinib maintenance therapy may have potential as standard of care for which subgroup of patients?

A

Patients with FLT3-TKD AML who are MRD-negative pre- or post-allo-HSCT

B

Patients with FLT3-TKD AML who are MRD-positive pre- or post-allo-HSCT

C

Patients with FLT3-ITD AML who are MRD-negative pre- or post-allo-HSCT

D

Patients with FLT3-ITD AML who are MRD-positive pre- or post-allo-HSCT

IDH1/2 inhibitors

Enasidenib, an IDH2 inhibitor, showed a manageable safety profile with preliminary activity as maintenance therapy in a phase I trial,41 with a phase II trial (NCT04522895) underway.42 Ivosidenib, an IDH1 inhibitor, has also shown promising efficacy and safety as maintenance therapy following HSCT.43

HMA combination therapies

HMA-based therapies have been specifically investigated in patients with high-risk AML. However, HMA monotherapy, such as 5-azacitidine, failed to show survival benefits after transplant in high-risk AML or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).44 Combination strategies have therefore been explored, with low-dose decitabine plus recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (rhG-CSF) effective in preventing high-risk AML relapse after allo-HSCT in a phase II trial.45 Azacitidine in combination with eprenetapopt (APR-246), a p53 reactivator, was also found to be well tolerated and showed encouraging survival outcomes in patients with TP53-mutated AML/MDS in a phase II trial.46 In the phase III RELAZA2 (NCT01462578) trial, an MRD-guided pre-emptive therapy with azacitidine prevented or substantially delayed hematologic relapse in patients with high-risk AML who were MRD-positive.47

There are further clinical trials of post-allo-HSCT maintenance therapy in AML that are ongoing; notably, mocravimod, a novel synthetic sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator, has received orphan drug designation and is currently under investigation in the phase III MO-TRANS trial (NCT05429632) to improve outcomes after allo-HSCT in patients with hematologic malignancies.48 The phase III AMADEUS trial (NCT04173533) of oral azacitidine and the phase III VIALE-T trial (NCT04161885) of venetoclax and azacitidine as post-transplant maintenance strategies are underway. A personalized maintenance approach using oral decitabine plus physician’s choice of a molecularly targeted second agent is also being evaluated in a phase Ib trial (NCT05010772).49

Clinical considerations

Post-remission maintenance therapy should be a part of the standard of care for all patients with AML, 50 and advocated to all patients with AML as part of ongoing clinical trials.1 When planning maintenance treatment, it is essential to take into account patient-related factors, including age, genomic profile, remission status, comorbid conditions, quality of life, and personal preferences, such as ease of administration and frequency of hospital visits.1 Additionally, the toxicity profile of the maintenance regimens and treatment duration should be considered, as prolonged exposure may increase disease resistance through subclonal heterogeneity, particularly if residual leukemia clones are not significantly reduced.1 Furthermore, the optimal duration of, and thus the safe discontinuation timepoint for, maintenance therapy remains unclear.50 Here, MRD monitoring during maintenance therapy may be useful, as it may inform the duration and intensity of treatment in clinic.1 Below, we summarise clinical guidelines and recommendations for the use of maintenance treatments in patients with AML.

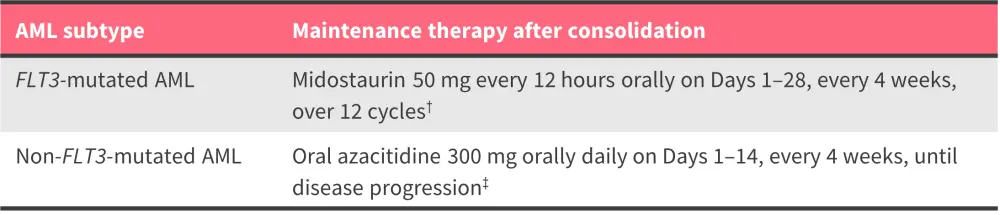

2022 ELN recommendations

In the 2022 ELN recommendations, patients who received midostaurin during induction and consolidation are suggested to continue this treatment in maintenance.4 Oral azacitidine is recommended for patients with non-FLT3-mutated AML post consolidation (Table 7).

Table 7. ELN 2022 recommendations for maintenance therapy in patients who are fit for intensive chemotherapy*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

*Data from Döhner et al.4

†The value of maintenance treatment with midostaurin remains uncertain.

‡Data regarding the role of oral azacitidine maintenance therapy in younger patients (<55 years) or patients with CBF AML are lacking; in addition, data are lacking for oral azacitidine after gemtuzumab ozogamicin-based or CPX-351 induction/consolidation therapy.

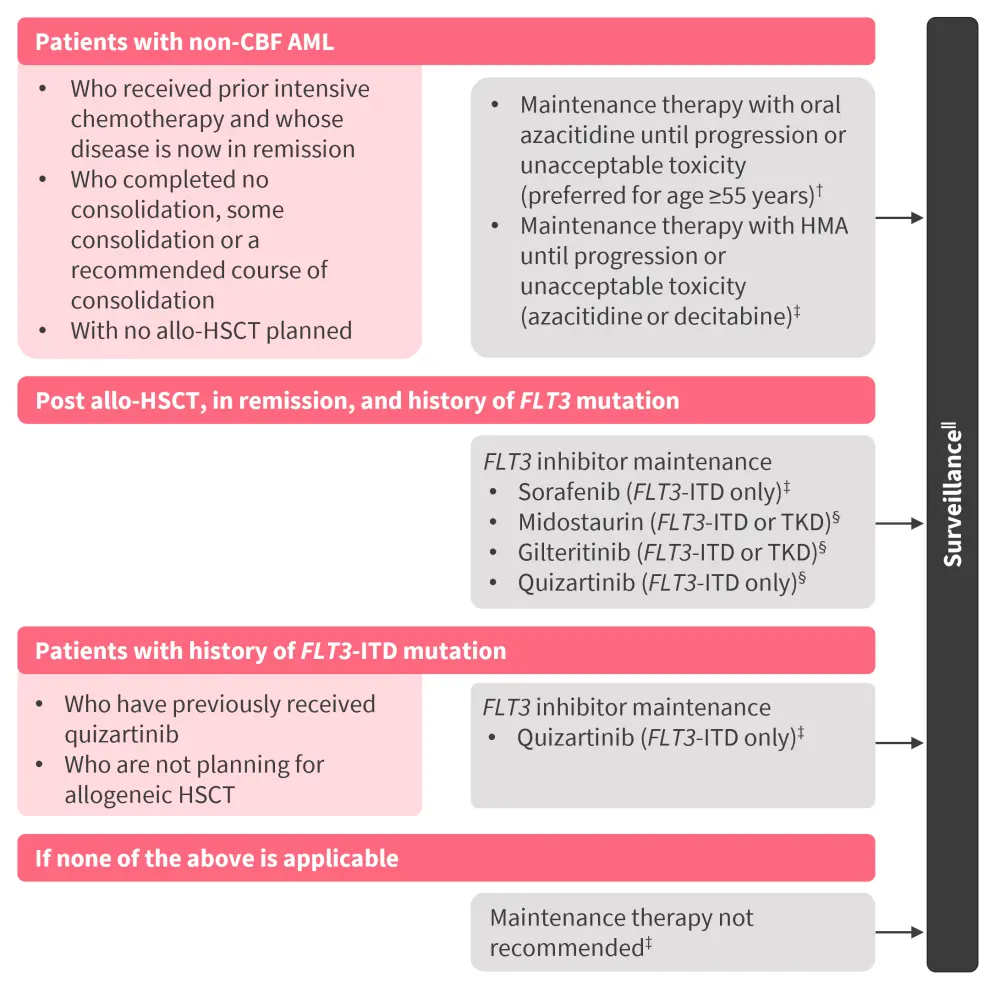

Figure 2. NCCN guidelines for maintenance therapy in AML*

allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CBF, core binding factor; ITD, internal tandem duplication; HMA, hypomethylating agent; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; TKD, tyrosine kinase domain.

*Adapted from NCCN.51

†Category 1: based on high-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate. This is not intended to replace consolidation chemotherapy. In addition, patients who are fit may benefit from HSCT in first complete response, and there are no data to suggest that maintenance therapy with oral azacitidine can replace HSCT.

‡Category 2A: based on lower-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

§Category 2B: based on lower-level evidence, there is NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

‖Studies are ongoing to evaluate the role of molecular monitoring in surveillance for early relapse.

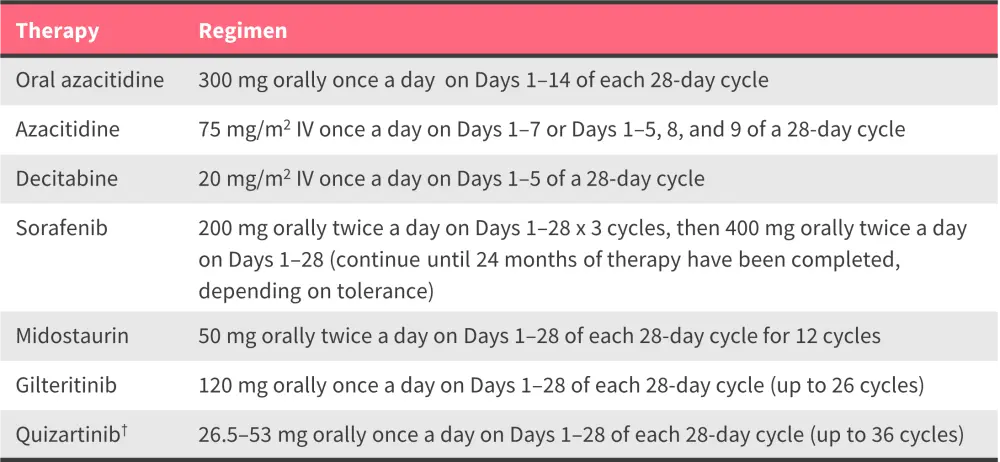

Table 8. NCCN guidelines for maintenance therapy in AML: Dose recommendations*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; IV, intravenous; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; QTcF, corrected QT interval Fridericia formula.

*Data from NCCN.51

†During Cycle 1, quizartinib should be administered at 26.5 mg orally once a day on Days 1–14 if QTcF is ≤450 ms. If QTcF remains ≤450 ms on Day 15, the dose should be increased to 53 mg orally once a day for the remainder of the 28-day cycle; the 26.5 mg dose should be maintained if QTcF was >500 ms at any point during induction or consolidation.

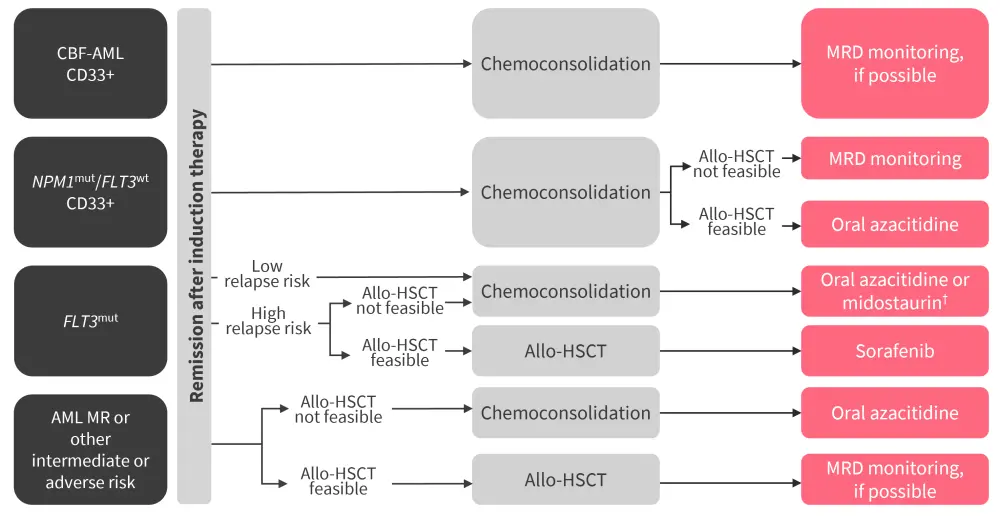

Figure 3. Overview of maintenance therapy in AML as per German consensus guidelines*

allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; MR, myelodysplasia-associated; MRD, measurable residual disease.

*Adapted from Rollig et al.52; †These guidelines were developed prior to the approval of quizartinib.

NCCN guidelines

The NCCN 2024 guidelines outline maintenance strategy options for different clinical scenarios, as depicted in Figure 2, with dosing information in Table 8.51 Among all treatment options, oral azacitidine is the only NCCN Category 1 preferred maintenance treatment option (based on high-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate).51

Regional guidelines

German Consensus guidelines

An overview of maintenance therapy in AML as per German consensus guidelines is shown in Figure 3. In patients with NPM1-mutated AML who are ineligible for or who choose not to proceed to allo-HSCT even after relapse, oral azacitidine is an effective maintenance treatment.52 Other patients with NPM1-mutated AML who are eligible for allo-HSCT should be closely monitored for NPM1-MRD to allow timely allo-HSCT in the event of molecular relapse.52 In patients with FLT3-ITD or -TKD mutation who are ineligible for allo-HSCT, maintenance with oral azacitidine is recommended until disease progression.52 If contraindications or intolerance arise, midostaurin may be used as an alternative,52 although of note these guidelines were developed prior to the approval of quizartinib. Among patients with FLT3-ITD AML who are eligible for allo-HSCT, sorafenib is recommended as the maintenance treatment, although of note these guidelines were developed prior to the approval of quizartinib.52 For myelodysplasia-associated AML or AML with intermediate or adverse risks, patients without an allo-HSCT option are recommended to be treated with oral azacitidine.52

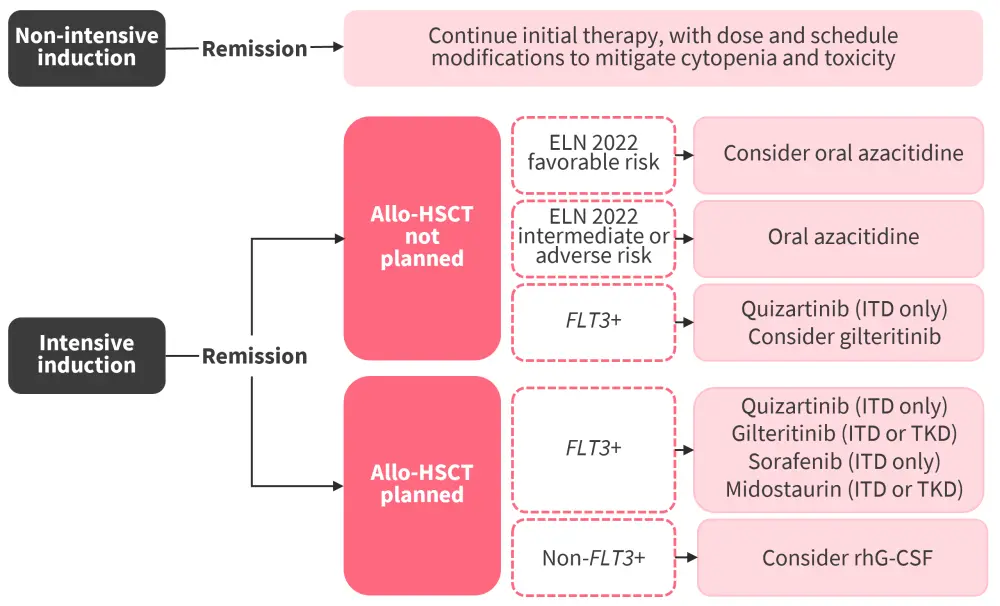

Use of maintenance treatments in clinical practice50

A model illustrating use of the above guidelines in clinical practice is shown in Figure 4. For patients with intermediate- and adverse-risk AML with allo-HSCT as the preferred consolidation, maintenance therapy should be considered as appropriate.1 In patients not proceeding to allo-HSCT who received low-intensity induction regimens, such as azacitidine + venetoclax or cytarabine + venetoclax, should continue these agents with dose and schedule adjustments to optimize tolerability.50,53 For those who received high-intensity induction and have targetable mutations, such as FLT3 or IDH, maintenance therapy should include the corresponding targeted inhibitors. Meanwhile, patients with favorable, intermediate, or adverse-risk disease who received intensive chemotherapy and are not proceeding to allo-HSCT, maintenance with oral azacitidine is recommended.50 Notably, none of the guidelines provide a fixed duration for oral azacitidine maintenance treatment.

Figure 4. Maintenance strategy for AML in clinical practice*

allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ELN, European LeukemiaNet; ITD, internal tandem duplication; rhG-CSF, recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; TKD, tyrosine kinase domain.

*Adapted from Roboz et al.50

Conclusion

The landscape of maintenance therapy in AML has rapidly progressed in recent years. A notable advancement in maintenance strategies was the FDA and EC approval of oral azacitidine monotherapy in older patients with AML who are not proceeding to allo-HSCT. Quizartinib is also approved alongside standard induction and consolidation therapies and as a maintenance monotherapy for adult patients with newly diagnosed FLT3-mutated AML. While midostaurin is not approved as a maintenance therapy, it is recommended to be used after consolidation for patients treated according to the RATIFY protocol. In addition, the combination of IL-2 and HDC is approved by the EC as a maintenance treatment in adults <60 years old with AML.

Despite this progress, identifying which patients will benefit most from these therapies remains challenging. Patients with favorable, intermediate, or adverse-risk disease who were treated with intensive chemotherapy and are not proceeding to allo-HSCT should be treated with oral azacitidine, whilst in those with targetable mutations, such as FLT3 or IDH, maintenance therapy should include the corresponding targeted inhibitors. Notably, maintenance treatment is strongly recommended in patients with NPM1 and FLT3-ITD co-mutations who are not undergoing allo-HSCT. Development of agents with enhanced targeting potential may lead to safer treatments and improved outcomes. In addition, future studies are needed to determine whether MRD-positive patients would also benefit from maintenance therapy, and to ascertain whether high-sensitivity MRD assays could aid in guiding the implementation and discontinuation of maintenance therapy for patients in molecularly defined subgroups. Furthermore, defining the appropriate timing for safe discontinuation of maintenance therapy is necessary.

Your opinion matters

After reading this educational resource, I commit to reviewing the latest advancements in the field of maintenance therapies for the treatment of patients with AML.

This educational resource was independently supported by Bristol Myers Squibb. All content was developed by SES in collaboration with an expert steering committee; funders were allowed no influence on the content of this resource.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content