All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know AML.

The aml Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the aml Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The aml and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The AML Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Syndax, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kura Oncology, AbbVie, and has been supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group.

Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View AML content recommended for you

The latest on oral azacitidine maintenance therapy in AML

Do you know... Oral azacitidine maintenance therapy is likely to have a significant relapse-free survival benefit vs placebo in patients with which of the following leukemic variants?

Effective maintenance therapy following intensive chemotherapy can prolong first complete remission and improve overall survival (OS) in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML); however, there has previously not been any standard maintenance strategy in AML.1 In the randomized phase III QUAZAR AML-001 trial (NCT01757535), oral azacitidine maintenance therapy was associated with a survival benefit vs placebo in patients aged ≥55 years with AML.2 Results from this trial have led to the use of oral azacitidine maintenance therapy in adult patients with AML in first complete remission following intensive chemotherapy who are ineligible for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT).1

Ravandi et al.1 recently published a post-hoc analysis of the QUAZAR AML-001 trial in the British Journal of Haematology. In addition, during the 65th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition, Lopes De Menezes2 and Mims3 discussed the use of oral azacitidine maintenance therapy in AML, and we are pleased to summarize these below.

Outcomes of patients who received subsequent therapy after discontinuing oral azacitidine1

In patients who discontinued treatment in QUAZAR AML-001, subsequent therapies received were recorded every month for the first year, and every three months thereafter. The median follow-up for survival outcomes was 56.7 months.

Key findings

- The distribution of patients across the first subsequent therapy (FST) types was similar between treatment arms (Table 1)

Table 1. FST received after treatment discontinuation in the QUAZAR AML-001 trial*

|

Aza, azacitidine; FLAG-Ida, fludarabine, cytarabine, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and idarubicin; FST, first subsequent therapy; HIDAC, high-dose cytarabine; HMA, hypomethylating agent; LDAC, low-dose cytarabine; MEC, mitoxantrone, etoposide, and cytarabine. *Adapted from Ravandi, et al.1 |

||

|

FST, % |

Oral-Aza (n = 134) |

Placebo (n = 173) |

|---|---|---|

|

Intensive chemotherapy |

43 |

45 |

|

FLAG-Ida and similar regimens |

19 |

24 |

|

MEC and similar regimens |

16 |

9 |

|

HIDAC |

3 |

4 |

|

Other intensive chemotherapies† |

5 |

8 |

|

Lower-intensity therapies |

49 |

46 |

|

HMA |

25 |

31 |

|

LDAC |

13 |

4 |

|

Other lower-intensity therapies‡ |

11 |

10 |

|

Best supportive care only§ |

6 |

6 |

|

Not classified‖ |

1 |

1 |

- From the time of randomization, OS was numerically longer in patients who received subsequent therapy in the oral azacitidine arm (median OS, 17.84 months) vs placebo (median OS, 12.88 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.64–1.04)

- From the time of FST, OS was similar between the oral azacitidine arm (median OS, 5.19 months) and placebo (median OS, 6.08 months; HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.85–1.38)

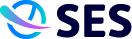

- Median OS from the time of FST by the type of treatment received is shown in Figure 1.

- In total, 48 patients proceeded to allo-HSCT after treatment discontinuation (oral azacitidine, n = 16; placebo, n = 32)

- When censoring all patients who underwent allo-HSCT at the time of transplant, median OS from randomization was improved in the oral azacitidine maintenance arm vs the placebo arm (24.84 vs 14.78 months; HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.55–0.86; p <0.001)

- When censoring only the six patients in the oral azacitidine arm who discontinued treatment to receive allo-HSCT while still in remission, OS outcomes remained the same (24.84 vs 14.78 months; HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.58–0.89; p = 0.0023)

Figure 1. Median OS from the time of FST by the type of FST received in the QUAZAR AML-001 trial*

CI, confidence interval; AZA, azacitidine; FST, first subsequent therapy; HMA, hypomethylating agent; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival.

*Data from Ravandi, et al.1

Author’s conclusion

Results from this post-hoc analysis suggest that oral azacitidine maintenance therapy does not negatively impact the survival outcomes of patients who receive subsequent therapies.

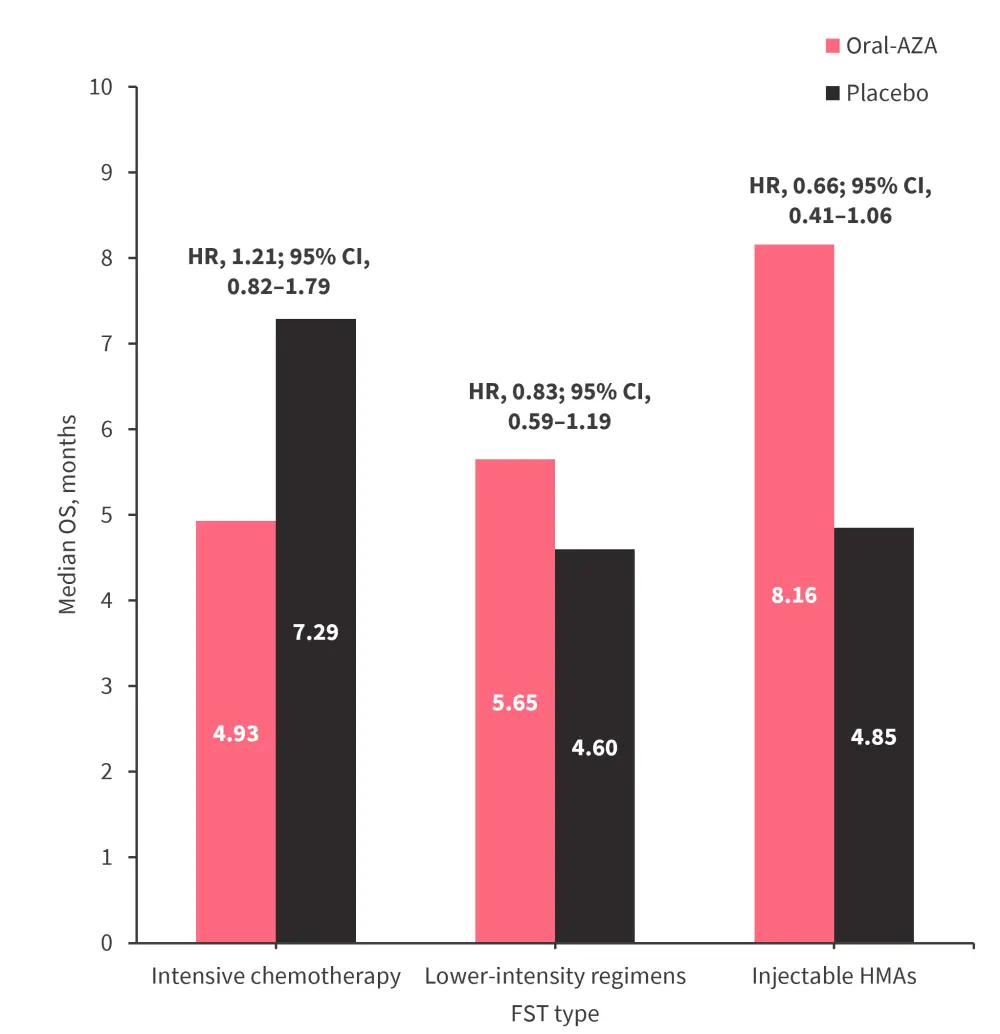

Mutational analysis from the QUAZAR AML-001 trial2

Targeted next-generation sequencing analysis was performed at baseline, Cycle 6, and relapse. Clonal variants classified as either leukemic, preleukemic, or age-related clonal hematopoietic variants using a variant classification algorithm incorporating associations between variant allele frequency and blast percentages over time.

Key findings

- Of the 310 patients included in this mutational analysis, 221 had detectable mutations at baseline

- The most frequently mutated genes at baseline were DNMT3A (28.4%), TP53 (15.5%), IDH2 (12.3%), TET2 (11.9%), SRSF2 (11.0%), IDH1 (6.1%), and ASLX1 (5.5%)

- There was a trend that showed improved relapse-free survival (RFS) with oral azacitidine maintenance vs placebo across the majority of baseline mutational subgroups

- This RFS benefit was maintained in leukemic DNMT3A (HR, 0.07; 95% CI, 0.02–0.23; p < 0.0001) and SRSF2 (HR, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.06–0.80; p = 0.021) variants; however, there was no benefit for preleukemic/age-related clonal hematopoietic variants in either treatment arm

- At relapse, the leukemic variant frequency was similar between treatment arms (Figure 2), and leukemic gene mutations present at relapse did not impact post relapse outcomes and were treatment-independent

Figure 2. Leukemic variants present ≥5% at relapse in either treatment arm in the QUAZAR AML-001 trial*

ASXL1, additional sex combs like 1; CEBPA, CCAAT enhancer binding protein alpha; DDX41, DEAD-box helicase 41; DNMT3A, DNA methyltransferase 3 alpha; FLT3-ITD, FMS-like tyrosine kinase-3 internal tandem duplication; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; NPM1, nucleophosmin 1; NRAS, neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog; RUNX1, runt-related transcription factor 1; SRSF2, serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 2; TET2, tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2; TP53, tumor protein p53; U2AF1, U2 small nuclear RNA auxiliary factor 1; WT1, Wilms' tumor gene 1.

*Adapted from Lopes De Menezes.2

Presenter’s conclusions

Oral azacitidine maintenance therapy may lead to improved RFS compared with placebo across most mutational subgroups detected at baseline, particularly in patients with leukemic DNMT3A and SRSF2 mutations. The mutational spectrum at relapse was similar between treatment arms, suggesting that oral azacitidine maintenance therapy does not alter mutational heterogeneity.

Intensive chemotherapy with oral azacitidine maintenance therapy vs venetoclax plus azacitidine3

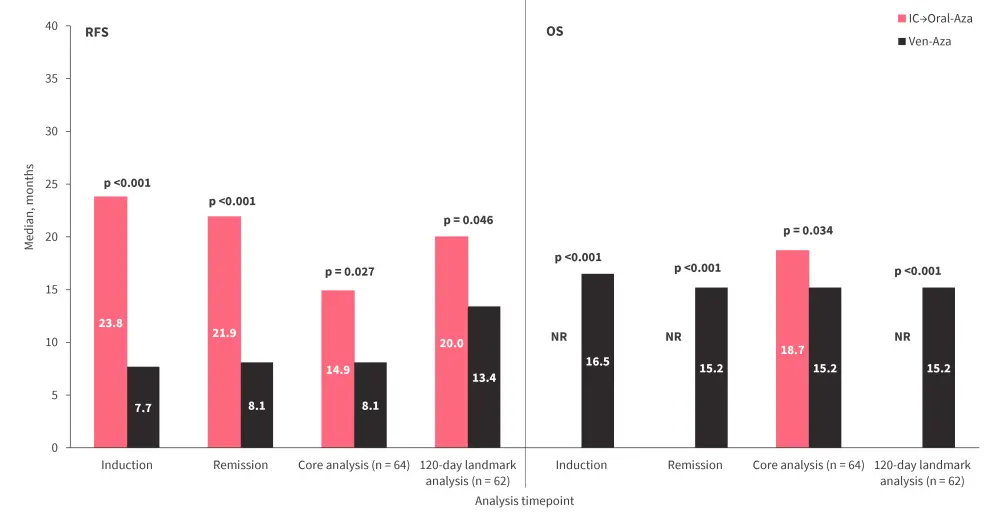

This retrospective analysis compared real-world outcomes in matched cohorts of patients with newly diagnosed AML who achieved remission after treatment with either intensive chemotherapy followed by oral azacitidine maintenance therapy or venetoclax plus azacitidine using the Flatiron Health longitudinal electronic health record database. Analyses were conducted from the following four different timepoints:

- induction;

- remission;

- from oral azacitidine maintenance initiation in the intensive chemotherapy cohort or from remission for the venetoclax plus azacitidine cohort (core analysis, n = 64); and

- from remission but limited to patients with >120 days of RFS following remission (120-day landmark analysis, n = 62)

Key findings

- Median RFS and OS were improved in patients who received intensive chemotherapy and then oral azacitidine maintenance vs those who received venetoclax plus azacitidine across all four of the time points analyzed (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Median RFS and OS by treatment received across therapeutic time points*

IC→oral-Aza, intensive chemotherapy followed by oral azacitidine maintenance therapy; NR, not reached; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival; Ven-Aza, venetoclax plus azacitidine.

*Data from Mims.3

Presenter’s conclusions

In this real-world retrospective analysis, intensive chemotherapy followed by oral azacitidine maintenance was associated with improved survival outcomes compared with treatment with venetoclax plus azacitidine across all study timepoints; however, the authors noted that the study was limited by the small and U.S. based patient population.

Overall conclusion

Results from these three analyses support the use of oral azacitidine maintenance therapy following intensive chemotherapy in adult patients with newly diagnosed AML.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content