All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know AML.

The aml Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the aml Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The aml and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The AML Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Syndax, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kura Oncology, AbbVie, and has been supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group.

The funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View AML content recommended for you

Recommendations from SIOG for the treatment of older patients with AML

Do you know... In the baseline disease assessment of older patients with AML, which of the following should be performed, independently of age?

Before recent advances, older patients aged 60 years or over rarely underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT); however, many patients aged at least 60 years now receive allo-HSCT, although it is still much less common in those aged 70 years and above. Additionally, such patients often require personalized treatment due to their diverse health and functional status.

Extermann et al.1 recently published recommendations from the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) for the treatment of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) aged 70 years or over in Journal of Geriatric Oncology; the AML Hub is pleased to summarize the key points below.

Methods1

Evidence around treatment and outcomes in patients aged at least 70 years old was reviewed by a task force using a GRADE approach and the strength of recommendations was based on group consensus, considering both evidence level and potential clinical impact.

General recommendation

The panel strongly recommended including older patients with AML in clinical trials due to limited evidence concerning treatment in this population.

What baseline assessment is needed?

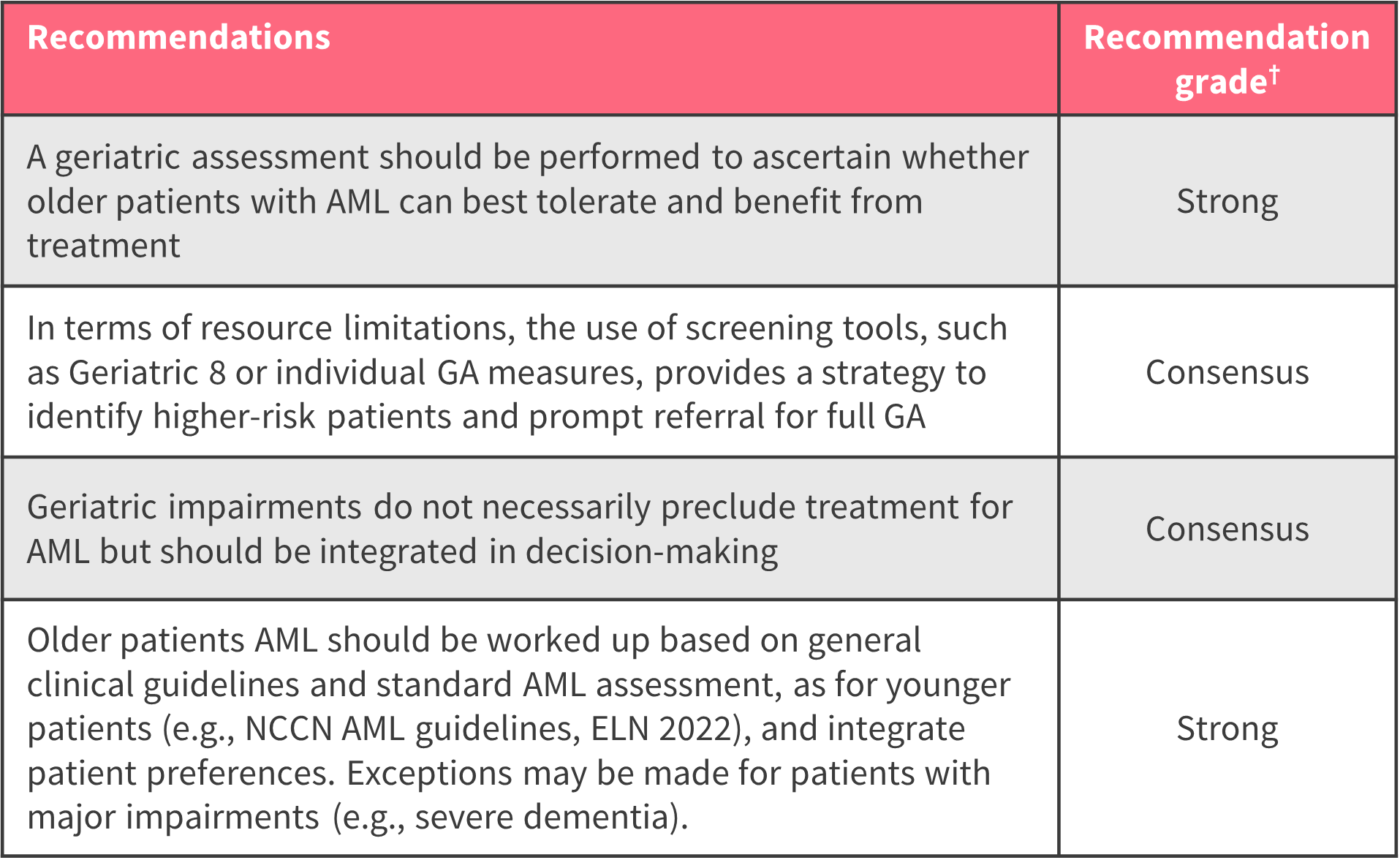

The panel identified increasing evidence supporting the need for geriatric assessment (GA) in older patients with AML, with GA also sensitive to functional and mental health status and correlated with survival outcomes. The prevalence of geriatric issues in these patients is high, and impaired cognitive and physical function are associated with reduced survival in patients undergoing intensive chemotherapy; however, in resource-limited settings, it can be challenging to implement routine GA.

Screening tools, such as the Geriatric 8 Questionnaire, have demonstrated prognostic utility and can be used in identifying older adults at higher risk of poor outcomes. In addition, standard AML assessment should be performed, regardless of age (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Recommendations for baseline assessment*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ELN, European LeukemiaNet; GA, geriatric assessment; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

*Adapted from Extermann, et al.

†Rated strong, moderate, or weak by group consensus, based on both the level of evidence and the potential clinical impact. If evidence was indirect, the level of recommendation was classed as “consensus”.

What should be used as frontline therapy?

Studies have shown that hypomethylating agents (HMAs) and intensive therapy vs low-dose chemotherapy and best supportive care improved overall survival in older patients; therefore, the panel recommended this regimen (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Recommendations for frontline therapy*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HMA, hypomethylating agent, RCT, randomized controlled trial.

*Adapted from Extermann, et al.1

†Rated strong, moderate, or weak by group consensus, based on both the level of evidence and the potential clinical impact; if evidence was indirect, the level of recommendation was classed as “consensus”.

What should be used postremission with or without transplant therapy?

There is limited data to inform an optimal management strategy in older patients after achieving remission, although consolidative allo-HSCT may improve survival in those with intermediate and unfavorable cytogenetics. Mild cognitive impairment is associated with higher rates of non-relapse mortality, while the use of a GA-informed multidisciplinary clinic is linked with shorter lengths of stay, fewer nursing-home admissions, reduced non-relapse mortality, and improved survival. Studies of maintenance therapies, including oral azacitidine, CPX-351, and cytarabine, suggest a survival benefit; therefore, the panel recommended that HMA-based maintenance therapy should be considered in patients achieving remission or in those who do not tolerate consolidation regimens (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Recommendations for postremission therapy*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; Ara-C, cytarabine; CR, complete remission; GA, geriatric assessment; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; HMA, hypomethylating agent; MRD, measurable residual disease.

*Adapted from Extermann, et al.1

†Rated strong, moderate, or weak by group consensus, based on both the level of evidence and the potential clinical impact. If evidence was indirect, the level of recommendation was classed as “consensus”.

What treatments are available for relapse?

Several retrospective studies have found intensive salvage therapy to extend survival in patients who were fit with non-adverse cytogenetics, the panel considered this as a bridge to transplant (Figure 4). The addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to salvage therapy is associated with improved outcomes; however, the potential toxicity of gemtuzumab ozogamicin remains uncertain.

Figure 4. Recommendations for relapse treatment*

GO, gemtuzumab ozogamicin; HMA, hypomethylating agent; IDAC, intermediate-dose cytarabine.

*Adapted from Extermann, et al.1

†Rated strong, moderate, or weak by group consensus, based on both the level of evidence and the potential clinical impact. If evidence was indirect, the level of recommendation was classed as “consensus”.

What are the available targeted therapies for older patients with AML?

Although many targeted agents are currently being investigated as part of ongoing clinical trials, several have not been assessed in older patients. The panel considered there to be enough evidence to support the use of a number of these therapies in this population (Figure 5). However, the choice of targeted therapy may be influenced by side effect profiles, pharmacokinetic interactions, pre-existing comorbidities, and interactions with other medications.

Figure 5. Recommendations for targeted therapies*

GO, gemtuzumab ozogamicin; HMA, hypomethylating agent; LDAC, low-dose cytarabine.

*Adapted from Extermann, et al.1

†Rated strong, moderate, or weak by group consensus, based on both the level of evidence and the potential clinical impact. If evidence was indirect, the level of recommendation was classed as “consensus”.

How does AML and its treatment affect patient-reported outcomes and function, and what supportive care interventions have been tested to enhance treatment tolerance?

The panel considered there to be a lack of evidence suggesting an association between either intensive or less intensive therapies and improved health-related quality of life in older patients, with studies to date reporting differing results. However, symptom burden and poor health-related quality of life are common in patients with AML, suggesting a need for treatments with improved tolerability and outcomes, particularly in older patients (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Recommendations for supportive care*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; GA, geriatric assessment; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; PRO, patient-reported outcome; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; QoL, quality of life.

*Adapted from Extermann, et al.1

†Rated strong, moderate, or weak by group consensus, based on both the level of evidence and the potential clinical impact. If evidence was indirect, the level of recommendation was classed as “consensus”.

Conclusion

The recommendations from SIOG provide a helpful guide for the management of older patients (70 years or older) with AML and highlight a population that is underrepresented in clinical trials. The SIOG expert panel strongly recommended generating direct evidence in this population, while integrating information from GA to improve external validity and outcomes. The SIOG expert panel also noted that combinations of HMAs and targeted therapies are rapidly evolving, and physicians should stay up to date on these developments and their impact on the treatment landscape.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with acute myeloid leukemia do you see in a month?