All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know AML.

The aml Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the aml Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The aml and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The AML Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Syndax, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kura Oncology, AbbVie, and has been supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group.

Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View AML content recommended for you

Editorial theme | Navigating the recent updates to the classification of AML: the International Consensus Classification

Do you know... The previous category of acute myeloid leukemia with myelodysplasia-related changes (AML-MRC) was heterogenous with certain limitations. Identify one limitation of the previous AML-MRC category.

There are currently two classification systems for acute myeloid leukemia (AML): the International Consensus Classification (ICC) of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias and the 5th edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Hematolymphoid Tumors. As part of our editorial theme on recent updates to the classification of AML, we are pleased to summarize a presentation by Hasserjian at the 2023 European Hematology Association (EHA) Congress.1 Hasserjian focuses mainly on the ICC, but also discusses the key differences between ICC and WHO classification.

Guiding principles of the International Consensus Classification of AML

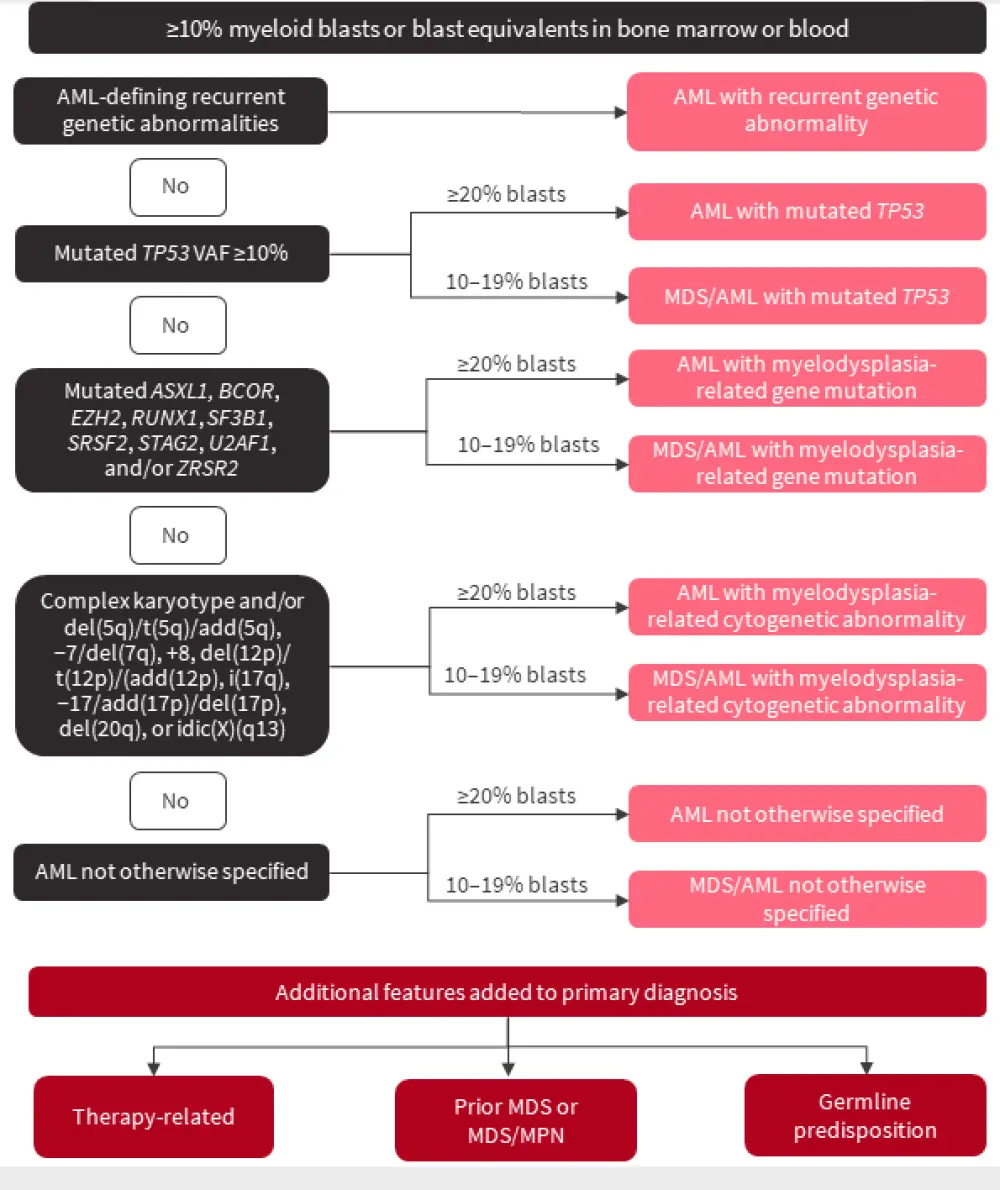

In the ICC, all AML subtypes are classified using a genetically-based hierarchy. Disease ontogeny aspects, such as disease progression, prior chemotherapy treatment, and underlying germline predisposition, can then be additionally applied as qualifiers to the genetic diagnosis. In addition, in TP53-mutated AML, ‘therapy-related’ can be added or, in AML with MDS-related gene mutations, progression from MDS can be added as a criterion to the diagnosis.

Contrary to the WHO classification, differential characterization, such as monocytic, myelomonocytic, erythroid, etc., can be recognized as a descriptor but does not establish specific disease subgroups. Furthermore, if an AML-defining genetic abnormality is not present, then the subtype is categorized as AML not otherwise specified. Within the ICC there is also acknowledgement of the biologic continuum between AML and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) with blast percentages between 10 and 19%, and that a fixed blast threshold of 20% is suboptimal in the differentiation between AML and MDS.

Understanding the hierarchy of the ICC of AML

An overview of the hierarchical classification of the ICC is shown in Figure 1, and further sections below cover specific categories within the ICC.

Figure 1. Hierarchical classification of the ICC*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms; VAF, variant allele frequency.

*Adapted from Döhner, et al.2

AML-defining genetic abnormalities

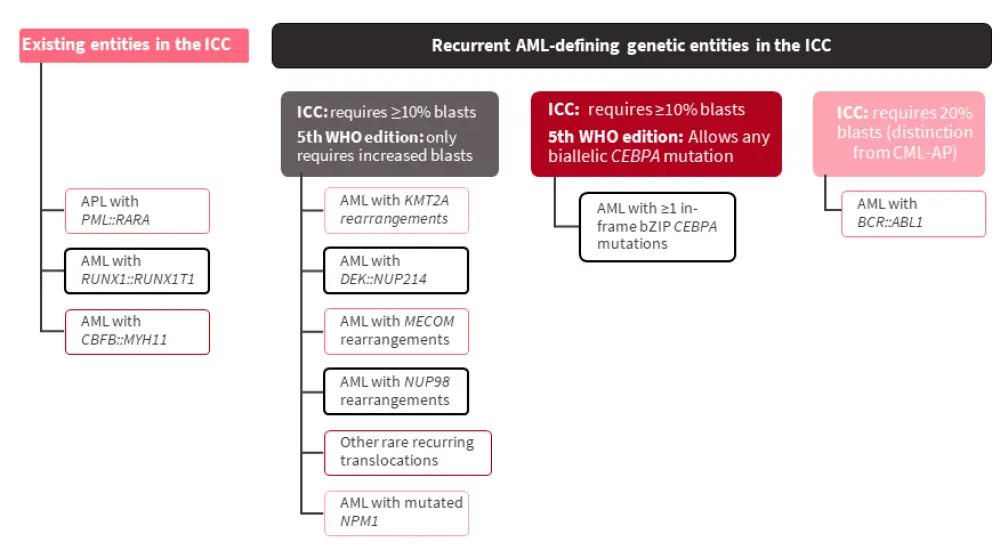

The recurrent AML-defining genetic entities listed in the ICC classification, and how they differ from the 5th WHO classification, are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Recurrent AML-defining genetic abnormalities in the ICC; all entities require the presence of ≥10% blasts in the bone marrow or blood*†

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia; CML-AP, chronic myeloid leukemia - accelerated phase; ICC, International Consensus Classification; WHO, World Health Organization.

*Adapted from Hasserjian.1

†Differences from the 5th edition of the WHO classification are highlighted with black boxes.

The definition of AML with biallelic CEBPA mutations has been modified to include ≥1 in-frame bZIP CEBPA mutation; this expresses a more homogenous, favorable prognostic group that is independent of mono- or bi-allelic mutation status.

In cases of <20% blasts, emerging data shows that hyperproliferative disease is defined by mutations such as NPM1, bZIP CEBPA, and CBF::R, regardless of initial blast percentage. Patients in this category treated with intensive chemotherapy show favorable outcomes; patients presenting with <20% blasts are infrequent and <10% even more uncommon. Another distinct group that defines hyperproliferative myeloid disease is the KMT2A::R, DEK::NUP214, MECOM::R; however, such patients with MDS or AML generally have poor outcomes despite being treated intensively.

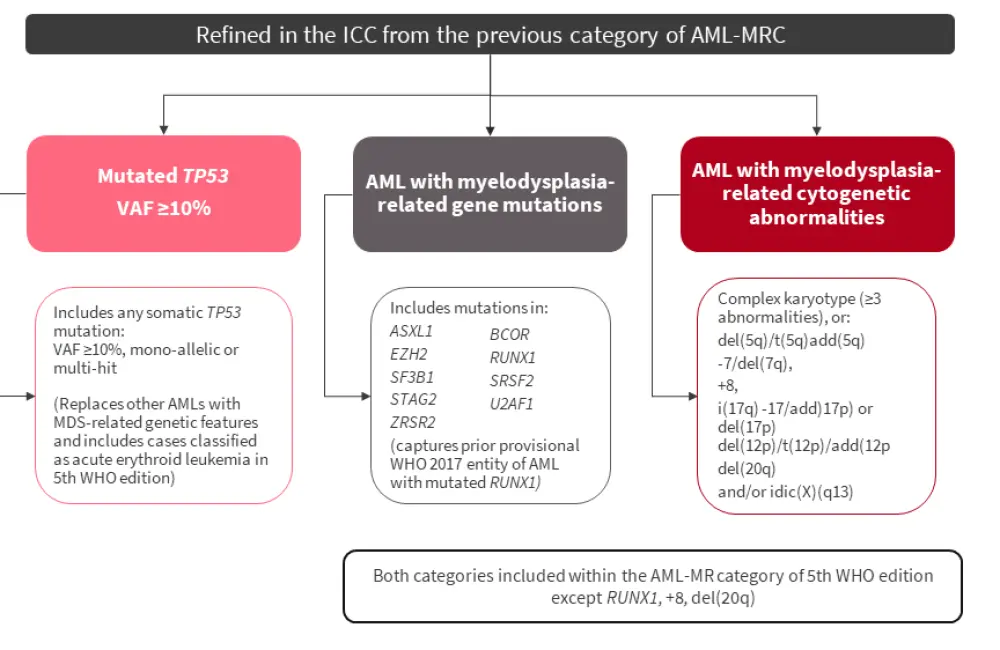

MDS with myelodysplasia-related changes (AML-MRC)

The previous category of AML-MRC was heterogenous, defined by a patient’s history (prior diagnosis of MDS or MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasms, regardless of genetics or treatment), cytogenetics, and morphology. It did not consider the impact of previous treatment, for example the association of hypomethylating agent failure and disease progression to AML with poor prognosis. In addition, the assessment of dysplasia varies in its reproducibility and may not be feasible in 30% of patients. Furthermore, AML-MRC may have limited prognostic value, even after considering genetic features. Notably, MDS that progresses to AML is strongly associated with mutations in SRSF2, SF3F2, U2AF1, ZRSR2, ASXL1, EZH2, BCOR, and STAG2; in de novo AML, these mutations indicate poor prognosis. Therefore, AML-MRC has been refined in the ICC, and replaced by ‘AML with MDS-related gene mutations’ and ‘AML with MDS-related cytogenetic abnormalities' (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Refinement of AML-MRC in the ICC*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; AML-MR, acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplasia-related; AML-MRC, acute myeloid leukemia with myelodysplasia-related changes; ICC, International Consensus Classification; VAF, variant allele frequency; WHO, World Health Organization.

*Adapted from Hasserjian.1

TP53 mutations

The ICC recognizes the need to classify TP53-mutated diseases as a single entity as risk stratification tools, such as the European LeukemiaNet (ELN) classification, do not adequately account for TP53 mutated-AML, which falls into the ELN adverse-risk AML category:

- TP53 mutations are associated with a higher likelihood of measurable residual disease negativity and are now considered to be a distinct biological category.

- TP53-mutated diseases demonstrate uniform aggression across various subtypes, and are not influenced by therapy-relatedness, complexity of karyotype, whether the diagnosis is MDS or AML, or blood counts.

Distinguishing AML from MDS

The blast threshold of 20% distinguishes AML from MDS, with >20% blasts associated with a higher likelihood of NPM1, CEBPA mutations, CBFB::MYH11, RUNX1::RUNX1T1, and KM2TA rearrangements. Progression from MDS to AML is also associated with acquisition of RAS pathways, IDH1 and IDH2 mutations; however, attainment of AML-type mutations may often occur before 20% blast levels. Furthermore:

- MDS with excess blasts 2 (MDS-EB2; 10–19% blasts) have genetic similarities to oligoblastic AML (20–29% blasts) and AML developed from MDS.

- In both MDS and AML, blast percentage and mutational burden are poorly correlated.

- Some patients with MDS-EB2 can be treated effectively with AML-type therapy.

Therefore, the revised MDS/AML category included in the ICC acknowledges that MDS and AML are biologically continuous, and a fixed blast percentage threshold between the two diseases may not be optimal. The revised MDS/AML category is only applicable to adult patients aged ≥18 years. Pediatric patients with 10–19% blasts should still be considered as MDS-EB. Patients in this category are eligible for both MDS and AML trials, allowing expansion of treatment options. Further studies are warranted to investigate which factors should drive treatment decisions in this category.

Differences between the 5th WHO classification and the ICC

After an analysis of the impact of new classifications on AML diagnosis, using data from 717 and 734 patients with non-therapy-related MDS and AML, respectively, who were diagnosed according to 4th WHO edition, overall agreement was found to be 86% between 5th WHO and ICC AML entities.3

Key differences between the 5th WHO classification and the ICC are:1

- Patients with 10–19% blasts continue to be classified as MDS-increased blasts (MDS-IB2).

- Any cases with increased blasts, without a 10% minimum threshold, qualify as having AML-defining genetic abnormalities.

- A blast count ≥20% is still required for CEBPA in-frame bZIP mutations to be AML-defining.

- MDS-related gene mutations, MDS-related cytogenetics, and any AML that has progressed from MDS or MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasms are grouped as a single entity under AML, myelodysplasia-related.

- There are some further differences in MDS-related cytogenetics and gene mutations between the two classifications.

- AML with mutated-TP53 is not recognized as a separate entity.

Conclusion

This summary of the ICC of AML, based on a presentation by Hasserjian, highlights the key changes to the AML classification hierarchy and outlines the differences from the 5th edition of the WHO classification. Although there is a reasonable agreement between the AML entities captured in the ICC and the WHO classification, there is potential for the two systems to be combined in the future and for any disparities to be reconciled.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content