All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know AML.

The aml Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the aml Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The aml and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The AML Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Syndax, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kura Oncology, AbbVie, and has been supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group.

The funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View AML content recommended for you

Triplet combination of HMA, FLT3 inhibitors, and venetoclax in FLT3-mutated newly diagnosed AML

FLT3 mutations are common in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and are associated with a greater risk of relapse and poor overall survival (OS).1 Pre-existing or emergent FLT3-ITD mutations are shown to play a role in resistance to venetoclax; FLT3 inhibition may increase sensitivity to venetoclax by increasing BCL-2 dependency and downregulating the anti-apoptotic protein MCL1. Combinations of venetoclax and FLT3 inhibitors are currently being investigated in the treatment of FLT3-mutated AML.1

In a retrospective analysis, Musa Yilmaz et al.1 compared clinical outcomes in older/unfit patients with newly diagnosed FLT3-mutated AML who were treated with either a doublet (low-intensity chemotherapy [LIC] plus FLT3 inhibitor) or triplet regimen (venetoclax combined with LIC plus FLT3 inhibitor). The results were recently published in Blood Cancer Journal, and we are pleased to summarize the key findings here.

In a previous article, we summarized the results of a phase I/II study investigating quizartinib combined with venetoclax and decitabine in FLT3-mutant AML.

Methods

Investigators collected data from 87 patients with newly diagnosed AML who:

- were older and/or unfit for intensive chemotherapy;

- had ≥2 bone marrow assessments (baseline, end of the first cycle of therapy, and later during treatment); and

- were treated with FLT3 inhibitor-based LIC regimens (doublet or triplet; Figure 1).

- FLT3 inhibitors included sorafenib (53%), quizartinib (23%), gilteritinib (14%), and midostaurin (10%).

- LIC regimens included hypomethylating agents (HMAs; decitabine or azacitidine), low-dose cytarabine (LDAC), and cladribine/LDAC. In the doublet cohort, HMA (83%) and cladribine ± LDAC (17%) were used, while all patients in the triplet cohort were given a HMA.

- Venetoclax was given in standard doses (400 mg/day or reduced dose in patients on strong CYP34A inhibitors).

Figure 1. FLT3 inhibitors use in the doublet and triplet treatment cohorts (N = 87)*

LIC, low-intensity chemotherapy.

*Adapted from Yilmaz, et al.1

In this analysis, complete remission (CR) and composite CR rates, measurable residual disease by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and multicolor flow cytometry (MFC), count recovery kinetics, early mortality, and median OS were compared between two cohorts.

Results

Baseline characteristics were similar between the doublet and triplet cohorts (Table 1), with the exception of:

- a significantly greater baseline FLT3-ITD allele ratio in the doublet cohort (0.71 vs 0.41 in the triplet cohort; p < 0.01)

- a significantly higher number of patients with an isolated FLT3-D835 in the triplet cohort (5 vs 0 in the doublet cohort; p < 0.01); and

- a significantly higher platelet count of 53 × 109/L in the triplet cohort (vs 27 × 109/L in the doublet cohort; p = 0.01).

Table 1. Patient characteristics in the two cohorts*

|

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ITD, internal tandem duplication; WBC, white blood cell. |

||

|

Characteristic |

Doublet cohort |

Triplet cohort |

|---|---|---|

|

Median age (range), years |

71 (51–83) |

69 (40–85) |

|

Age ≥75 years, % |

37 |

26 |

|

Male, % |

50 |

41 |

|

Type of AML, % |

|

|

|

De novo |

71 |

74 |

|

Secondary AML |

12 |

11 |

|

Therapy related |

17 |

15 |

|

Median WBC (range), × 109/L |

5.3 (0.3–164) |

4.2 (1–201) |

|

Median platelet count (range), × 109/L |

27 (3–326) |

53 (9–116) |

|

Peripheral blood blasts (range), % |

26 (0–98) |

19 (0–89) |

|

FLT3 mutation, % |

|

|

|

ITD only |

88 |

78 |

|

D835 |

0 |

18 |

Response

In the doublet cohort, there was no significant difference in CR/CRi, CR, FLT3-PCR negativity, or MFC negativity when response to first- and second-generation FLT3 inhibitors was compared.

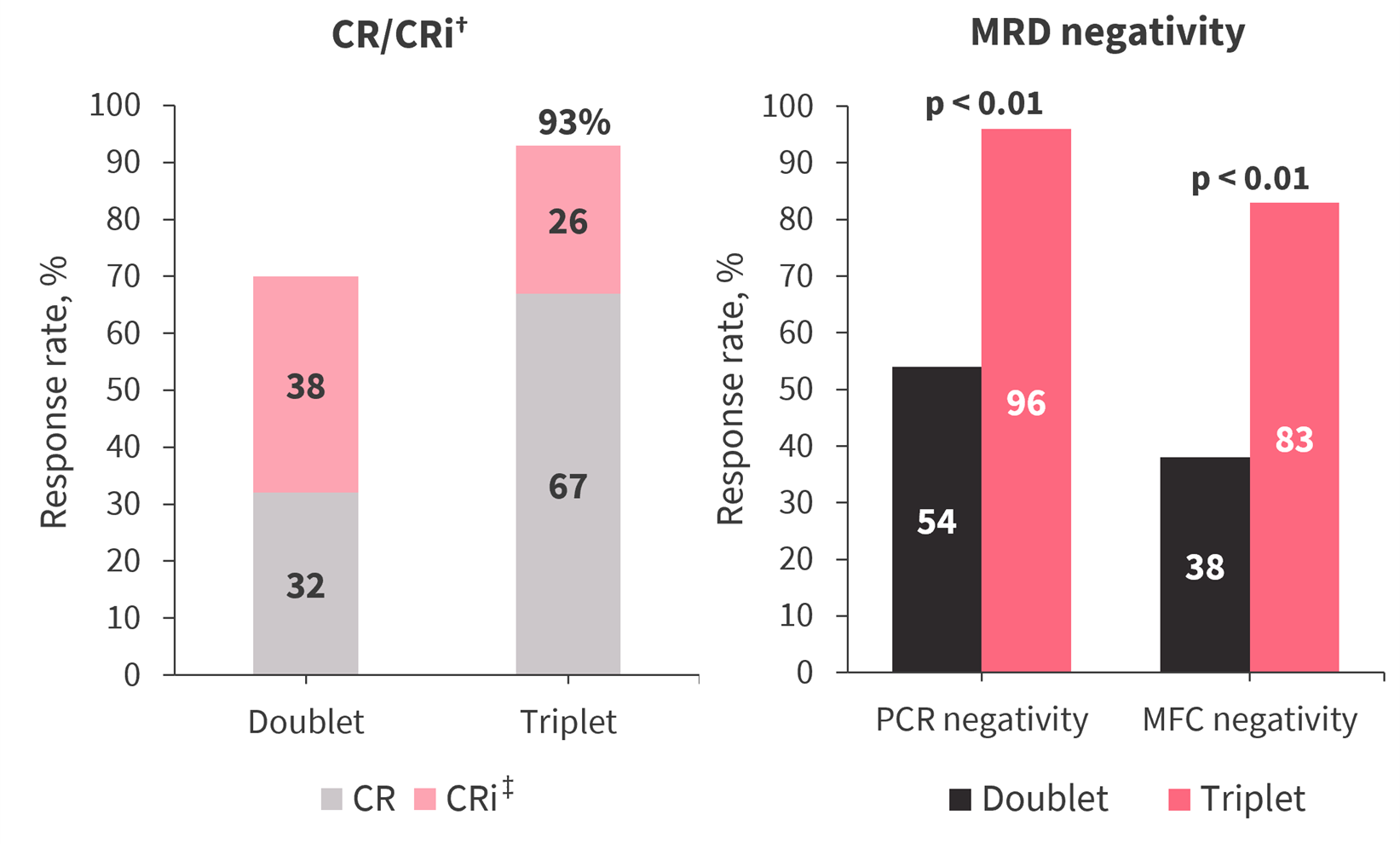

Figure 2 provides the comparative analyses of response between the doublet and triplet cohorts. The triplet regimen was associated with earlier responses occurring after a median of 1 cycle (vs 2 cycles in the doublet cohort) and significantly higher response rates. Responses after Cycle 1 were more frequent in the doublet cohort; 8% and 27% of patients achieved CR/CRi in Cycle 2 or beyond in the triplet and doublet cohorts, respectively.

Figure 2. Response rates in both cohorts*

CR, complete remission; CRi, CR with incomplete count recovery; MFC, multicolor flow cytometry; MRD, measurable residual disease; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

*Adapted from Yilmaz, et al.1

†p = 0.02.

‡p < 0.01.

Median time to absolute neutrophil count >500/mm3 and platelet count >50 × 109/L showed no significant difference between two cohorts. However, by Day 42, 74% and 28% of patients in the triplet and doublet cohorts, respectively, had a platelet count >50 × 109/L (p < 0.01).

In the triplet cohort, three patients in composite CR (11%) died due to infections and unknown reasons. In the doublet cohort, 12 patients (20%) died due to infection, an unknown reason, posttransplant complication, and intracranial hemorrhage. Treatment discontinuation due to treatment-related adverse events was required in one (4%) and four (6%) patients on the triplet and doublet regimens, respectively.

Survival

The median duration of follow-up in the triplet and doublet cohorts was 12 months and 63 months, respectively (p < 0.01).

- Median OS (not reached vs 9.5 months; p < 0.01) and relapse-free survival (p = 0.03) were significantly longer in patients receiving triplet versus doublet regimen.

- Median OS in patients treated with triplet regimen, doublet regimen with a second-generation FLT3 inhibitor, and doublet regimen with a first-generation FLT3 inhibitor was not reached, 15.7 months, and 8.7 months, respectively (p < 0.01).

- There was no significant difference in median OS between patients treated with first- or second-generation FLT3 inhibitors in the doublet or triplet cohorts.

- High FLT3-ITD allele ratio (≥0.5) was not found to have a significant impact on median OS.

While patients with MFC negativity had a significantly longer survival than those with MFC positivity (21 months vs 14.8 months, respectively; p = 0.02), PCR negativity did not have a significant impact on survival. Significantly higher MFC negativity rates in the triplet cohort may have translated into earlier and better hematologic recovery, higher CR rates, and longer survival.

A total of 14 patients (16%) underwent transplant in CR1, with a median time to transplant of 4 months. The median OS in these patients was not reached, compared with 19 months in those who did not undergo transplant (p = 0.01). A significantly greater number of patients in the triplet cohort proceeded to transplant compared with the doublet cohort (30% vs 10%; p = 0.02), which may be attributed to higher CR/CRi and CR rates. Patients who underwent transplant in the doublet cohort had significantly longer survival (not reached) compared with those who did not.

Conclusion

This study suggests that in older/unfit adult patients with newly diagnosed AML the triplet combination of HMA, FLT3 inhibitor, and venetoclax is associated with significantly higher response and measurable residual disease negativity rates, as well as longer OS, with no increase in 60-day mortality or deaths in remission, compared with the doublet combination of HMA and FLT3 inhibitors. In the doublet cohort, the CR/CRi rates and median OS were comparable with first- and second-generation FLT3 inhibitors. Of note, the number of patients who achieved absolute neutrophil count >500/mm3 and platelet count >50 × 109/L were higher in the triplet cohort, which may be a result of significantly greater CR rate.

The authors noted that future investigations of this triplet regimen in larger, prospective trials may include evaluations of the duration of venetoclax in the first and later cycles, dose of FLT3 inhibitors, timing of bone marrow assessment, duration of therapy with triplet regimen before switching to another therapeutic approach, and safety.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with acute myeloid leukemia do you see in a month?