All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know AML.

The aml Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the aml Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The aml and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The AML Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Syndax, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kura Oncology, AbbVie, and has been supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group.

Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View AML content recommended for you

Venetoclax plus 10-day decitabine in chemotherapy-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed or R/R AML

The prognosis of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in older patients is usually poor, due to the presence of comorbidities and the early mortality associated with induction therapy. These factors render these patients unfit for intensive chemotherapy and result in the undertreatment of many patients.1 The combination of venetoclax, a selective B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitor, with hypomethylating agents (HMAs) is now considered the standard of care in patients aged ≥75 years or those ineligible for intensive chemotherapy, following the results of the phase III VIALE-A trial among other studies. Decitabine is a cytosine analogue that has demonstrated higher response rates when administered for 10 days, compared to a 5-day schedule, in patients with high-risk AML.1

Courtney DiNardo et al. investigated the impact of venetoclax plus 10-day decitabine on outcomes in high-risk patients with newly diagnosed (ND) or relapsed/refractory (R/R) AML, in a single-center phase II trial (NCT03404193). The results of this study were recently published in The Lancet Haematology1 and are summarized below.

Study design

Patients groups included:

- Older patients (>60 years) with ND AML who were unfit for intensive chemotherapy.

- Patients (>18 years) with secondary AML with a history of prior hematological disorder including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML).

- Patients (>18 years) with R/R AML.

- Patients (>18 years) with high-risk MDS or CMML with 10–20% bone marrow blasts or R/R after HMAs.

- Patients (>18 years) with ND AML with poor-risk, complex karyotype or TP53 mutation.

The article provided results from the first three patient groups.

The treatment-naïve patients were those with ND AML or untreated secondary AML with a prior hematological disorder. The previously treated category included those with secondary AML with previous therapy for MDS or CMML and those with R/R AML.

Patients were deemed eligible based on the following criteria:

- Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status <3.

- White blood cell count <10 × 109/L.

- Adequate end-organ function.

Methods

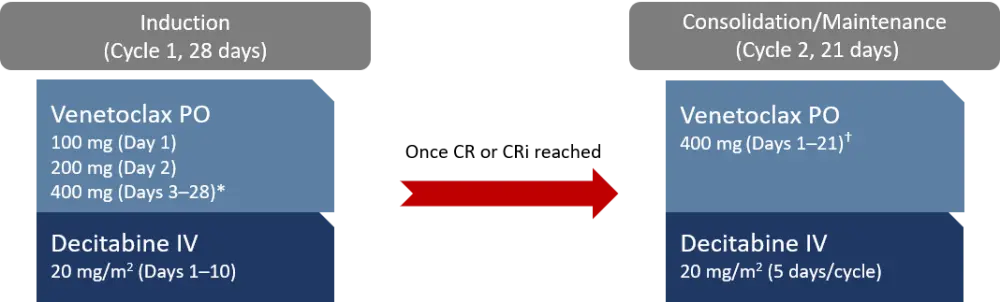

Study treatment is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Treatment scheme1

CR, complete remission; CRi, CR with incomplete hematological recovery; IV, intravenous; PO, oral.

*Venetoclax was stopped on Day 21 if bone marrow analysis revealed aplasia or remission with <5% blasts.

†Venetoclax duration was reduced to 14, 10, or 7 days once in remission.

The primary endpoint was overall response rate, including complete remission (CR), CR with incomplete hematological recovery (CRi), partial response, and morphological leukemia-free state per the modified International Working Group criteria. Secondary endpoints included duration of response, disease-free survival, overall survival (OS), safety, the proportion of patients with hematological improvement in platelets, hemoglobin, or absolute neutrophil count (ANC), those with > 50% reduction in blasts, or those requiring stem cell transplantation.

Patients

The total number of patients enrolled to the study was 168, with a median age of 71 years (range, 65–76). Most patients (n = 70) had ND AML. The proportion of patients with European LeukemiaNet (ELN) intermediate or adverse cytogenetic risk was similar among groups. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics among patient groups1

|

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ELN, European Leukemia Net; HMA, hypomethylating agent; IC, intensive chemotherapy; ND, newly diagnosed; R/R, relapsed/refractory; sAML, secondary AML; SCT, stem cell transplantation; WBC, white blood cell. |

||||

|

Characteristic |

ND AML |

Untreated sAML |

Treated sAML |

R/R AML |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Median age, years (range) |

72 (70–78) |

71 (68–76) |

70 (65–76) |

62 (43–73) |

|

ECOG PS, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

Diagnosis, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

ELN 2017 risk group, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

Median WBC count, × 109/L (range) |

2.9 (1.8–4.8) |

4.3 (2.0–6.7) |

2.0 (1.0–5.4) |

3.6 (1.6–6.0) |

|

Peripheral blood blasts, % (range) |

10 (1–30) |

4 (0–27) |

8 (1–27) |

24 (3–58) |

|

BM blasts, % (range) |

45 (23–62) |

36 (18–61) |

32 (25–54) |

34 (22–64) |

|

Median number of previous therapies (range) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (1–2) |

2 (1–3) |

|

Previous HMAs, n (%) |

— — |

— |

25 (89) |

25 (45) |

|

Previous IC, n (%) |

— |

— |

5 (18) |

42 (76) |

|

HMAs and IC, n (%) |

— |

— |

3 (11) |

12 (22) |

|

SCT, n (%) |

— |

— |

8 (29) |

18 (33) |

|

Mutations, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

Outcomes

- The overall response rate among all patients was 74%, with a CR/CRi rate of 61%.

- CR/CRi rate was high among all ELN risk groups in patients with ND AML: 90% in favorable-, 100% in intermediate-, and 75% in the adverse-risk group.

- Among 119 patients with evaluable bone marrow on Day 21 of Cycle 1, 55% of patients had bone marrow blasts of ≤5%.

- Flow cytometry measurable residual disease negativity was achieved by 58% of responding patients (95% CI, 49–67).

Median follow-up was 16 months (95% CI, 12–18). Outcomes among groups are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Response and survival outcomes among subgroups1

|

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; CI, confidence interval; DoR, duration of response; CR, complete remission: CRi, CR with incomplete hematological recovery; MLFS, morphological leukemia-free state; MRD, minimal residual disease; ND, newly diagnosed; NR, not reached; R/R, relapsed/refractory; sAML, secondary AML. |

||||

|

Outcome, % (95% CI) |

ND AML |

Untreated sAML |

Treated sAML |

R/R AML |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Overall response rate |

89 (79–94) |

80 (55–93) |

61 (42–76) |

62 (49–74) |

|

CR |

66 (54–76) |

40 (20–64) |

21 (10–40) |

24 (14–36) |

|

CRi |

19 (11–29) |

27 (11–52) |

18 (8–36) |

18 (10–30) |

|

CR/CRi |

84 (74–91) |

67 (42–85) |

39 (24–56) |

42 (30–55) |

|

No response |

11 (6–21) |

20 (7–45) |

36 (21–54) |

27 (17–40) |

|

BM blasts ≤ 5%* |

67 (53–79) |

80 (49–94) |

38 (21–59) |

44 (28–61) |

|

MRD negativity* |

67 (54–79) |

40 (17–69) |

47 (25–70) |

54 (36–71) |

|

MLFS |

4 (2–12) |

13 (4–39) |

21 (10–40) |

18 (10–30) |

|

Median OS, months (95% CI) |

18.1 (10–NR) |

7.8 (2.9–10.7) |

6.0 (3.4–13.7) |

7.8 (5.4–13.3) |

|

Median DoR, months (95% CI) |

NR (9.0–NR) |

5.1 (0.9–NR) |

NR (2.5–NR) |

16.8 (6.6–NR) |

|

Median time to response, months (95% CI) |

1.5 (1.3–1.7) |

1.3 (0.9–2.2) |

1.7 (1.1–2.6) |

1.8 (1.4–2.0) |

|

Second cycle of 10-day decitabine, % |

11 |

13 |

29 |

29 |

Mutation subgroup analysis showed the following CR/CRi rates in treatment-naïve patients:

- NPM1 mutated: 95% (95% CI, 77–99)

- IDH1/IDH2 mutated: 84% (95% CI, 61–94)

- NRAS/KRAS mutated: 74% (95% CI, 51–88)

- TP53 mutated: 69% (95% CI, 50–84)

Multivariate analyses showed that not achieving CR, previous HMAs or intensive chemotherapy treatments, TP53 mutation, and diagnosis of secondary AML were all associated with a higher risk of death, while secondary AML and TP53 mutation were also associated with higher risk or relapse.

Safety

Among 261 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), 193 were Grade 3–4 events and six were Grade 5 (infection with absolute neutrophil count <1.0 × 109/L, n = 5; renal failure, n = 1). The most common Grade 3–4 TEAEs were infections, with Grade 3–4 neutropenia occurring in 47% and febrile neutropenia in 29%. The most common infections included pneumonia, sepsis or bacteremia, and cellulitis. Tumor lysis syndrome developed in 2% of patients with a 100% recovery rate.

The most common Grade ≥3 TEAEs are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Most common Grade ≥3 TEAEs across all patient groups1

|

ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CNS, central nervous system; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event. |

|||

|

TEAE, n (%) |

Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

Grade 5 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Infection with ANC <1.0 × 109/L |

77 (46) |

2 (1) |

5 (3) |

|

Febrile neutropenia (ANC <1.0 × 109/L) |

49 (29) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

Infection with ANC >1.0 × 109/L |

11 (7) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

Tumor lysis syndrome |

3 (2) |

1 (1) |

0 (0) |

|

Fever (ANC >1.0 × 109/L) |

0 (0) |

1 (1) |

0 (0) |

|

CNS hemorrhage |

0 (0) |

1 (1) |

0 (0) |

|

Renal failure |

0 (0) |

2 (1) |

1 (1) |

At data cut-off, 46% of patients were still alive. Across all patients, 30-day and 60-day mortality rates were 3.6% (95% CI, 1.7–7.8) and 10.7% (95% CI, 6.9–16.9), respectively. The causes of death were neutropenic fever (n = 5) and renal failure from acute tubular necrosis (n = 1). The five neutropenic deaths (3%) were considered to be treatment related.

Treatment discontinuation occurred in 75% of patients with the most common reasons being no response (21%), relapse (20%), or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (14%). Decitabine dose reduction occurred in 13% of patients with ND AML, 13% with untreated secondary AML, 4% with treated secondary AML, and 5% with R/R AML.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that venetoclax plus 10-day decitabine is tolerable and leads to high response rates, particularly in patients with de novo ND AML. However, it did not improve outcomes to the same degree in therapy-related AML or AML with prior hematological disorders. This may be attributed to 10-day decitabine being too myelosuppressive for patients with myelodysplasia.

Response rates were also high in patients with high-risk cytogenetics, with a CR/CRi rate of 90% in RUNX1 AML, 90% in FLT3 AML receiving FLT3 inhibitors, and 70% in TP53 AML. Responses were durable for patients with NPM1, IDH1/IDH2, or FLT3 mutations, but remission was similar to that achieved with 5-day decitabine regimen in TP53 AML. These results suggest that venetoclax plus 10-day decitabine may be a potential salvage therapy before stem cell transplantation in older patients (>60 years) with untreated or previously treated AML. Further large-scale, prospective trials are needed to validate these results.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content