All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know AML.

The aml Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the aml Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The aml and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The AML Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Syndax, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kura Oncology, AbbVie, and has been supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group.

Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View AML content recommended for you

The NOPHO-DB-SHIP consortium recommendations for supportive care in pediatric AML

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) accounts for ~20% of acute leukemia cases in children and adolescents, with higher overall survival rates improving in recent years.1 This improvement is attributable to intense standard chemotherapy and advances in supportive care. However, there is lack of consensus among various international groups regarding best practice.1

In planning for a new trial protocol (CHIP-AML 2022) in pediatric patients with AML, the Nordic-Dutch-Belgian-Spain-Hong-Kong-Israel-Portugal (NOPHO-DB-SHIP) consortium formed a group spanning 14 countries to address issues around supportive care in pediatric AML.1 The NOPHO-DB-SHIP supportive care group met to discuss the topics at three meetings in 2021–2022 and achieved a consensus level of 75–100%.1 Here, we summarize their recommendations published in Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy by Arad-Cohen, et al.1 They include general management of children and adolescent patients with AML, with a specific focus on hyperleukocytosis, tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), coagulation abnormalities and bleeding, infection, typhlitis, malnutrition, cardiotoxicity, and fertility preservation.

General recommendations

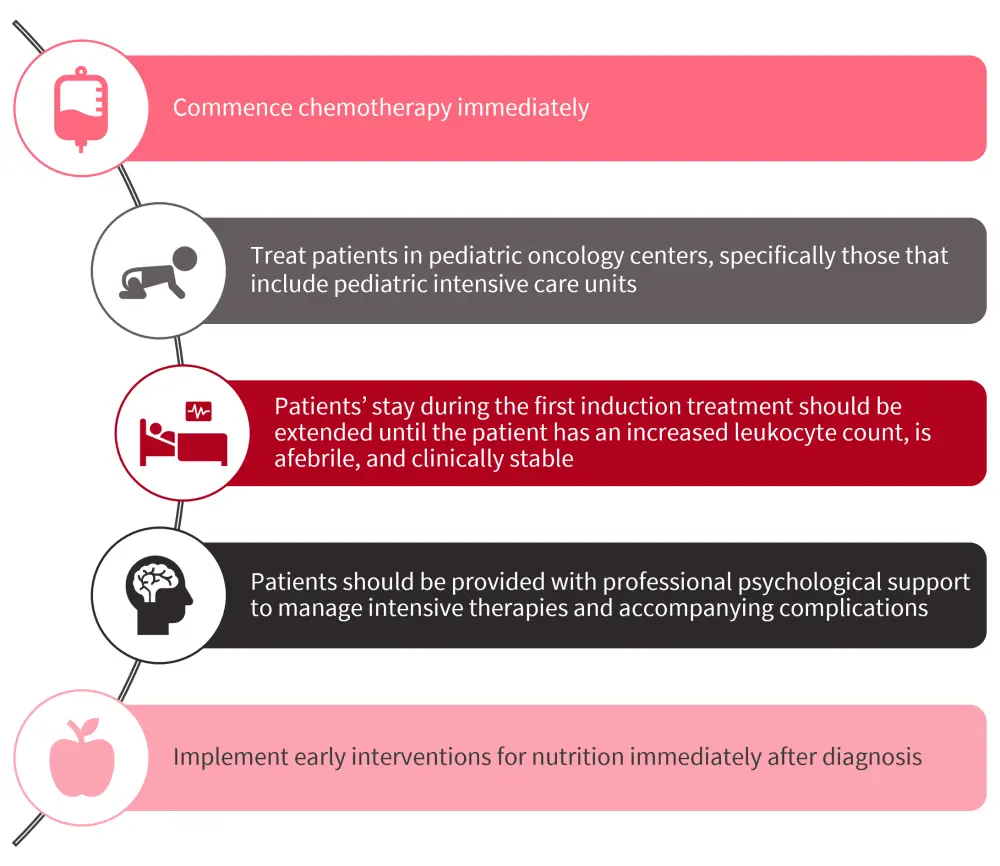

Pediatric patients with AML are at risk of complications, such as bleeding, respiratory distress, upper airway obstruction, pulmonary infiltration, and renal and metabolic disturbances; therefore, several general recommendations should be considered (Figure 1).

Figure 1. General supportive care recommendations*

*Data from Arad-Cohen, et al.1

Hyperleukocytosis

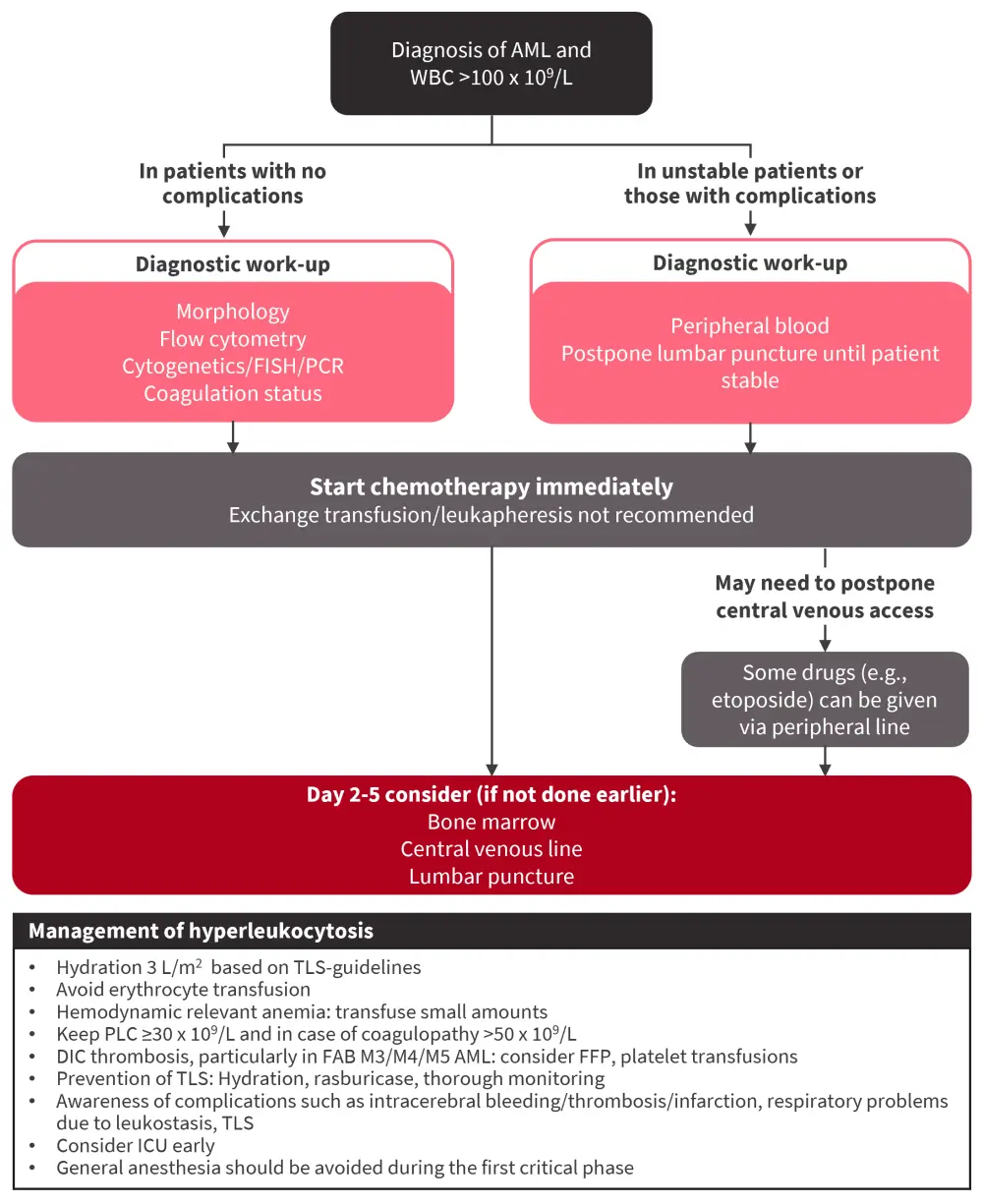

Hyperleukocytosis is defined as a white blood cell count >100 x 109/L and is associated with a higher risk of leukostasis, which can lead to complications, such as bleeding, thrombosis, seizures, stroke, and lung involvement with respiratory distress. There is also an increased risk of renal dysfunction and metabolic disturbances exacerbating TLS due to hyperleukocytosis.

The use of exchange transfusion and leukapheresis for the treatment of hyperleukocytosis is not recommended by the consortium due to the risks and lack of benefit; however, full-dose chemotherapy should be commenced immediately (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Management of hyperleukocytosis*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; ET, exchange transfusion; FAB, French-American-British; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; ICU, intensive care unit; LP, leukapheresis; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PLC, platelet count; M3, acute promyelocytic; M4, myelomonocytic; M5, monocytic; TLS, tumor lysis syndrome.

*Adapted from Arad-Cohen, et al.1

TLS

Although TLS is less common in patients with AML compared with those with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, it can still occur. Patients with a white blood cell count >50–100 x 109/L, organomegaly, pre-existing hyperuricemia, lactate dehydrogenase ≥2-times the upper normal limit, increased creatinine, renal and/or urinary tract disorders, severe dehydration, and FAB-M5 (a French-American-British classification of acute monocytic leukemia) have an increased risk of TLS.

- Recognition and early treatment of TLS are essential.

- Allopurinol, an oral xanthine oxidase inhibitor that blocks the metabolism of hypoxanthine and xanthine to uric acid, reducing the incidence of obstructive uropathy, is recommended in most patients.

- In patients with TLS or high tumor burden, intravenous rasburicase (a recombinant urate oxidase is recommended), allowing early initiation of chemotherapy. However, close monitoring and immediate treatment are needed in case of electrolyte disturbances, such as hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcemia.

- In symptomatic hypokalemia, particularly in patients with monocytic leukemias, aggressive replacement with parenteral potassium is required.

Coagulation abnormalities

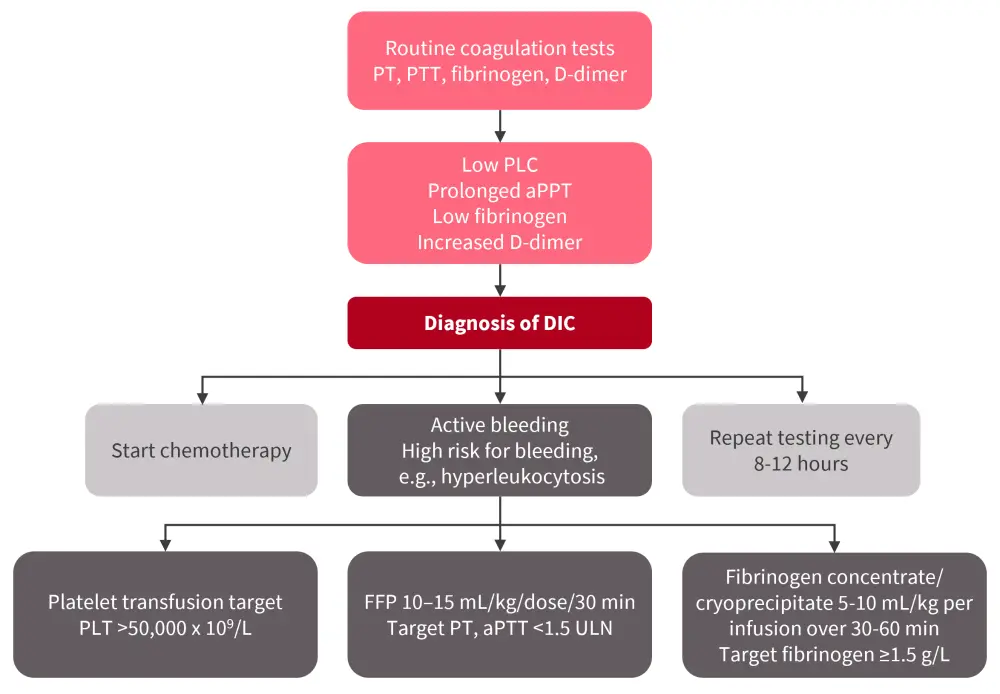

Pediatric patients with AML have high incidences of coagulation disorders, such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of DIC are shown in Figure 3, and include the following:

- Maintaining the platelet count >50 x 109/L in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia or monocytic AML, who have a higher bleeding risk during the diagnostic phase, until there is no active bleeding and coagulation parameters are stabilized

- Administering fresh frozen plasma (10–15 mL/kg) at levels <1.5-times the upper normal limit and fibrinogen concentrate or cryoprecipitate to maintain fibrinogen level ≥1.5 g/L

Thromboprophylaxis and the use of heparin are not recommended. In patients with thromboembolism, treatment should be given on an individual basis due to lack of evidence-based guidelines.

Figure 3. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation*

aPPT, activated partial thromboplastin time; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; PLC, platelet count; PPT, partial thromboplastin time; PT, prothrombin; ULN, upper limit normal.

*Adapted from Arad-Cohen, et al.1

Infections

Pediatric patients with AML are at an increased risk of bacterial, fungal, and viral infections, exposing them to fatal complications.

Bacterial prophylaxis

- Antibacterial prophylaxis in pediatric AML is controversial and not recommended for routine use; depending on the individual risk profile, considering risk-benefit evaluation, epidemiology, and after discussion with pediatric infectious disease experts, it may be appropriate for select patients.

- A randomized trial investigating teicoplanin prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis in pediatric patients with AML is currently ongoing within the CHIP-AML 2022 trial; further prospective studies are warranted.

Fungal prophylaxis

The risk of invasive fungal disease is increased in pediatric patients with AML due to age, prolonged neutropenia, and intensive chemotherapy.

- Patients should be offered a prophylaxis regimen with anti-mold therapy, such as azole or an echinocandin.

- The choice of prophylactic antifungal agent will depend on local epidemiology, drug interaction potential, side effect profile, age, compliance, cost, and drug availability.

Antiviral prophylaxis

- All children diagnosed with AML should be screened for herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV).

- Antiviral prophylaxis may be offered if recurrent reactivations of HSV or VZV occur.

- Varicella zoster immunoglobulin should be administered within 72 hours of VZV exposure.

- Acyclovir may be used for VZV symptom prevention.

- No specific recommendations for the prevention of respiratory viruses, except social isolation.

- Recurrence of COVID-19 should be considered, especially during the induction stages of therapy.

- Pediatric patients aged >12 years should receive intravenous remdesivir for 3 days or oral nirmatrelvir-ritonavir for 5 days.

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the use of bebtelovimab in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic children with AML with COVID-19 infection.

- Tixagevimab and cilgavimab can be administered prophylactically in patients aged ≥12 years and weighing ≥40 kg.

- Family and caregivers should be vaccinated against influenza and SARS-CoV-2 to avoid infection spread.

- Drug availability in each country and expertise in infectious disease should be considered when determining treatment.

Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia

- Prophylaxis with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole during the entire period of chemotherapy and up to 6 weeks after the end of therapy is recommended.

- In patients with marrow toxicity or adverse effects due to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, pentamidine, dapsone, or atovaquone should be considered.

Neutropenic fever

Due to the risk of sepsis, neutropenic fever in pediatric patients with AML is considered a medical emergency, requiring evaluation and empirical treatment of all patients immediately.

- Patients should be treated with an antipseudomonal β-lactam, a fourth-generation cephalosporin, or a carbapenem antibiotic.

- In patients who are clinically unstable or have resistant infections, a glycopeptide should be added, and a second anti-gram-negative agent should also be considered.

- De-escalation or discontinuation of antibiotics in stable patients (afebrile ≥24 hours) is advised, based on local infrastructure and patients’ follow-up.

- In patients with persistent fever for ≥96 hours, a fungal work-up should be done irrespective of positive bacterial culture. Empirical antifungal treatment with caspofungin or liposomal

amphotericin B should be considered, based on the local policy, imaging, and laboratory findings.

G-CSF and granulocyte transfusion

- The use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is not recommended in pediatric patients with neutropenic fever, due to the potential increased risk of relapse; however, it may be considered in patients who are neutropenic with recorded bacterial or fungal infection that is not responsive to broad spectrum antimicrobial agents.

- Granulocyte transfusion should be considered only in selected situations, for example in patients with prolonged neutropenia or severe infection resistant to broad spectrum antimicrobial or antifungal therapy.

Typhlitis

This is a severe abdominal complication that occurs in ~14–38% of neutropenic patients and can lead to mucosal damage.

- Antibiotics covering a broad spectrum of Gram-negative, Gram-positive, and anaerobic bacteria, such as β-lactam monotherapy or a combination with an aminoglycoside, should be considered, along with local resistance pattern.

- Surgeons are likely to advise the withholding of oral nutrition for 24–48 hours, with surgery reserved for situations such as bowel perforations or massive gastrointestinal bleeding.

Nutrition

The consortium does not recommend a neutropenic diet for pediatric patients with AML, as these diets have significant restriction on the types of food an individual is able to consume and there is lack of evidence to justify their use in this population.

Cardiotoxicity

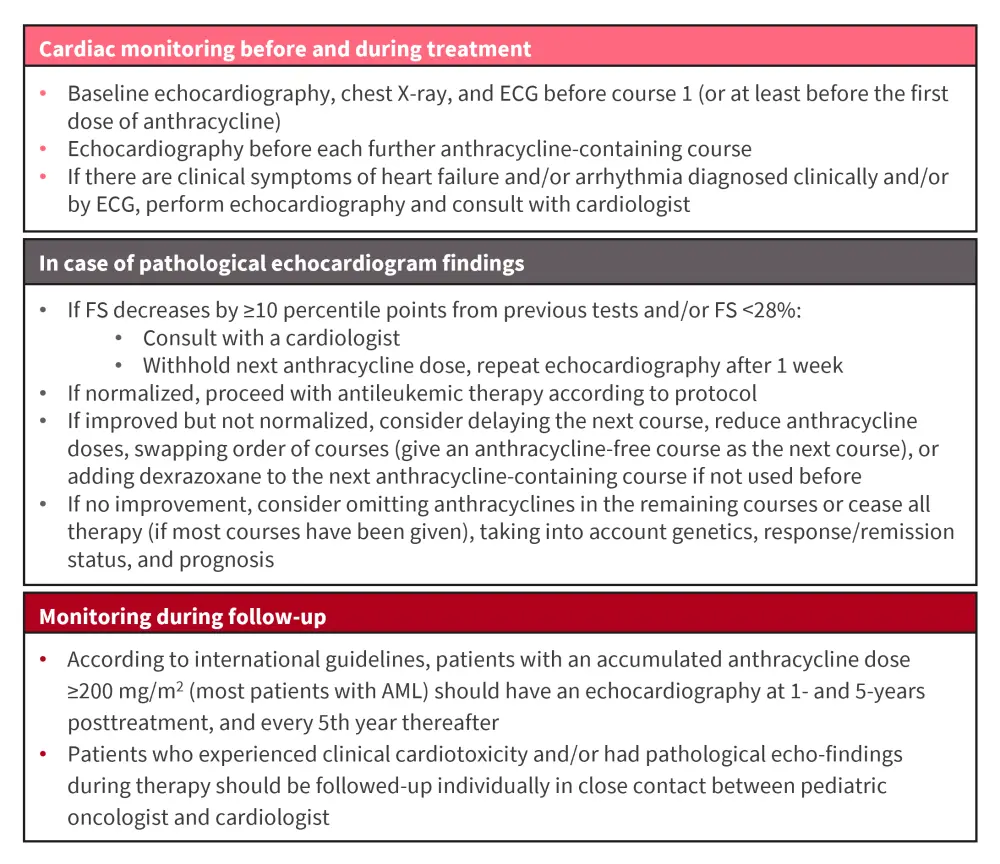

Acute, early-onset, and late cardiotoxicity may occur in pediatric patients with AML leading to poor survival outcomes. Pediatric patients are at a higher risk of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity even at lower threshold doses.

- The use of dexrazoxane, a cardioprotective drug, is supported by the consortium for prevention of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity, depending on drug availability and local policy.

- Cardiac monitoring should be performed during and after AML therapy (Figure 4).

- Global longitudinal strain can be used to detect early subclinical myocardial dysfunction; however, due to the variability in normal values between software packages, its use in routine practice is limited, and therefore the consortium recommends improved methods for early detection of subclinical decline in cardiac function.

Figure 4. Recommended cardiac monitoring during and after AML treatment*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ECG, electrocardiogram; FS fractional shortening.

*Adapted from Arad-Cohen, et al.1

Fertility preservation

Most fertility guidelines consider the risk of permanent gonadotoxicity secondary to conventional AML therapy to be <20%, although if myeloablative conditioning is undergone then this risk increases to >80%. Therefore, children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may be offered gonadal biopsy cryopreservation, with the following considerations:

- Fertility preservation options, including ovarian tissue cryopreservation, should not be offered to female pediatric patients at diagnosis or to those who do not undergo transplantation.

- However, in female patients proceeding to transplant, fertility preservation and restoration strategies should be offered and tailored to the individual patient’s circumstances.

- Gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone may help to prevent menorrhagia in female patients with thrombocytopenia secondary to chemotherapy.

- Long-term follow-up to assess endocrine and reproductive function is helpful, to identify of survivors who might benefit from postchemotherapy or posttransplant fertility preservation options.

- Postpubertal male patients should be offered sperm cryopreservation before chemotherapy.

- Sperm should be collected prior to treatment initiation to avoid compromising quality.

- In prepubertal male patients, extraction of immature testicular tissue should only be performed pretranplant in a clinical trial setting.

Conclusion

The recommendations by the NOPHO-DB-SHIP consortium will facilitate further improved cure rates in a highly susceptible pediatric population with AML. These recommendations are also essential for the implementation of the new CHIP-AML 2022 protocol across 14 countries. Further research is needed to improve the initial management of hyperleukocytosis, define the role of prophylactic antibiotics, and improve cardioprotection, including investigating the beneficial effect of dexrazoxane. As novel agents advance, unique toxicities will emerge, defining new supportive care guidelines in the future.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content