All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know AML.

The aml Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the aml Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The aml and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The AML Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Syndax, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kura Oncology, AbbVie, and has been supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group.

Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View AML content recommended for you

Do you know... When considering NGS-MRD testing prior to allo-HSCT, which of the following outcomes is not associated with MRD status?

Measurable residual disease (MRD) has proven to be highly sensitive in predicting survival outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1 The AML Hub has previously reported findings on the potential role of next-generation sequencing (NGS)-MRD in prognosis, particularly when determining eligibility for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Patients with persistent MRD negativity are thought to be good candidates for autologous HSCT, or chemotherapy, whereas those with persistent MRD positivity may benefit from allogeneic HSCT (allo-HSCT). Despite these findings, MRD currently plays a limited role in real-world clinical practice, due to issues such as lack of standardization, generalizability, and overall clinical utility.1

At the 2022 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, Hourigan, et al.1 reported findings from the pre-MEASURE study, which comprises a nationwide data analysis of MRD testing in real-world clinical practice in patients with AML in first complete remission (CR1) prior to first allo-HSCT. We summarize the key points below.

Methods

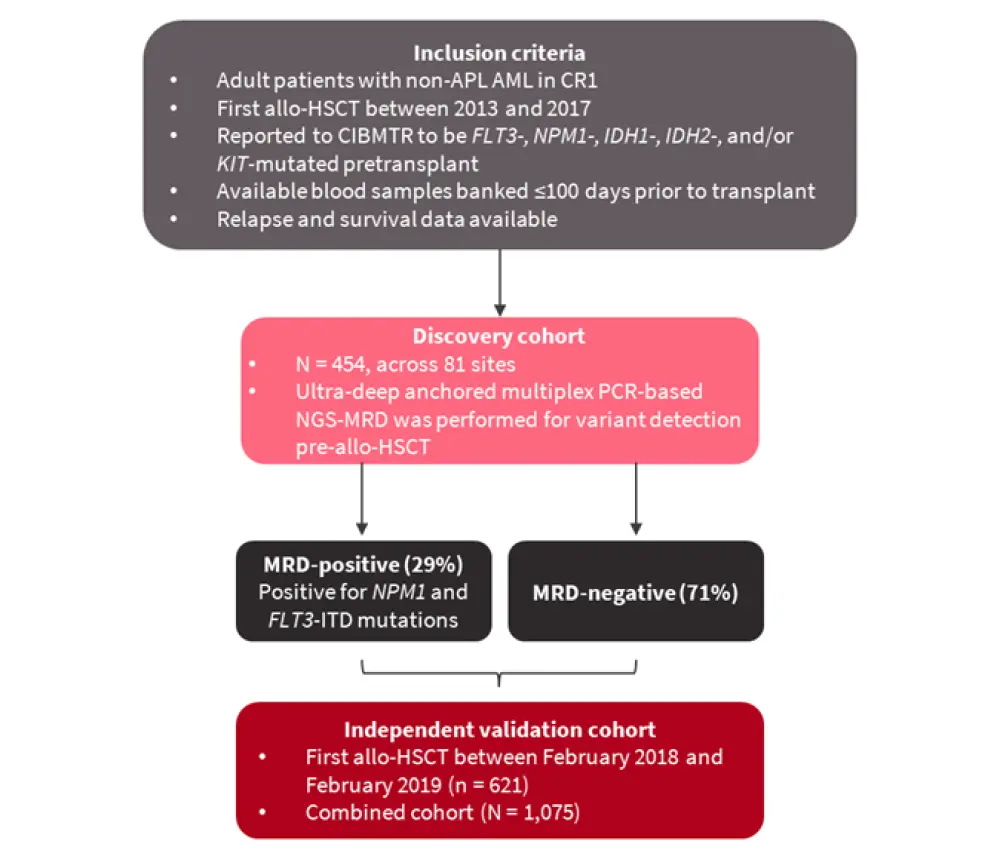

The inclusion criteria and design of the pre-MEASURE study are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Inclusion criteria and design of the pre-MEASURE study*

Allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CIBMTR, Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research; CR1, first complete remission; MRD, measurable residual disease; NGS, next-generation sequencing; non-APL AML, non-acute promyelocytic leukemia AML.

*Adapted from Hourigan, et al.1

Results

Patient characteristics for the discovery and validation cohorts are summarized in Table 1. The most common mutations across both cohorts were FLT3-ITD (n = 276) and NPM1 (n = 239). Over half of patients had myeloablative conditioning (MAC) prior to allo-HSCT.

Table 1. Patient characteristics*

|

ELN, European LeukemiaNet; FLT3-ITD, FLT3-internal tandem duplication; HCT-CI, hematopoietic stem cell transplant-specific comorbidity index; MAC, myeloablative conditioning; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning. |

||

|

Characteristic |

Discovery cohort |

Validation cohort |

|---|---|---|

|

Median age, years (range) |

56.8 (18.4–75.6) |

58.2 (18–80.5) |

|

Female, % |

52 |

53 |

|

Race, % |

||

|

Caucasian |

82 |

86 |

|

Other |

17 |

11 |

|

Missing |

1 |

3 |

|

HCT-CI, % |

||

|

0 |

17 |

21 |

|

1–2 |

35 |

28 |

|

>2 |

46 |

50 |

|

Missing |

2 |

1 |

|

Karnofsky score, % |

||

|

<90 |

41 |

40 |

|

≥90 |

58 |

60 |

|

Missing |

1 |

0 |

|

ELN risk group, % |

||

|

Favorable |

19 |

25 |

|

Intermediate |

48 |

41 |

|

Adverse |

32 |

34 |

|

Missing |

0 |

0 |

|

FLT3-ITD, n |

||

|

FLT3-ITD + NPM1 mutation |

144 |

173 |

|

FLT3-ITD + NPM1 wild type |

98 |

128 |

|

FLT3-ITD + NPM1 unknown |

34 |

31 |

|

Conditioning regimen, % |

||

|

MAC |

56 |

57 |

|

RIC with melphalan |

19 |

19 |

|

RIC other |

25 |

24 |

Prognostic impact of NGS-MRD pre-allo-HSCT

When considering specific mutations, FLT3-ITD and NPM1 were selected in the univariate analysis as prognostic factors for relapse (p < 0.0001 for both mutations), and so were carried forward in MRD testing for the discovery cohort. Mutations in FLT3-TKD, KIT, IDH1, and IDH2 were not significantly associated with relapse, and so were not carried forward.

Pre-allo-HSCT NGS-MRD was not predictive of non-relapse mortality, but was associated with overall survival (OS), relapse, and relapse-free survival (RFS) (p < 0.0001 for all comparisons).

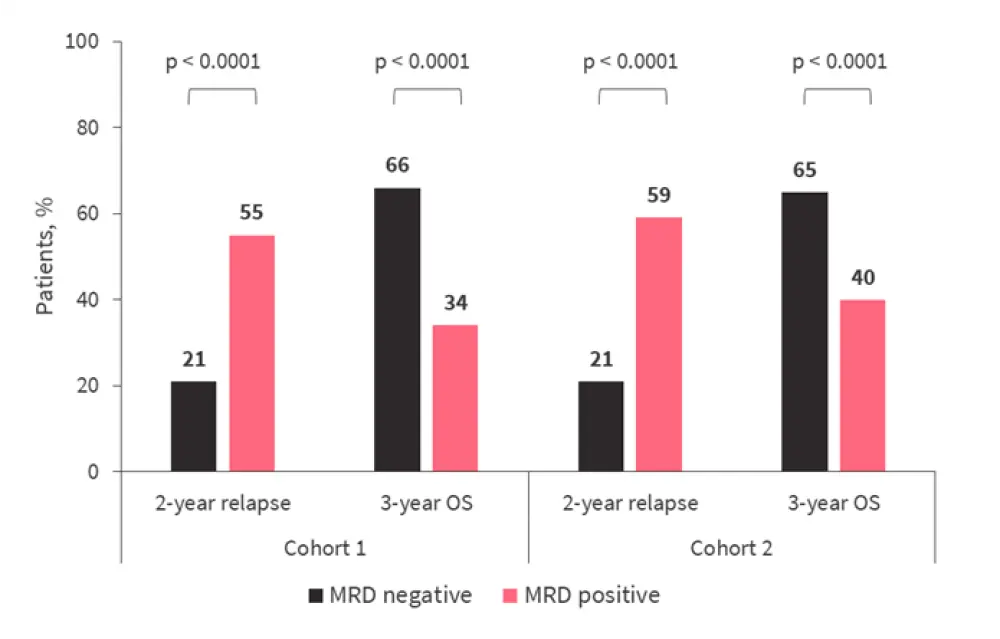

When an independent validation cohort (n = 621) was analyzed, in which patients underwent allo-HSCT between February 2018 and February 2019, no significant differences in patient characteristics were observed compared with the original discovery cohort (Table 1). The prognostic impact of MRD pretransplant was similar in both cohorts for OS and relapse (Figure 2).

Figure 2. 2-year relapse rates and 3-year OS in the discovery and validation cohorts*

MRD, measurable residual disease; OS, overall survival.

*Adapted from Hourigan, et al.1

Prognosis in subgroups

Within the combined cohort (N = 1,075):

- NGS-MRD positivity was associated with higher rates of relapse and poorer OS in both younger (<60 years; p < 0.0001 for both) and older (≥60 years; p < 0.0001 for both) patient subgroups.

- Increased relapse and decreased OS rates were also noted in patients who were MRD-positive for residual FLT3-ITD mutation (n = 608; p < 0.001 vs MRD-negative), and in those positive for NPM1 mutations (n = 531; p < 0.001 vs MRD-negative).

- Detection of NPM1 mutations was also associated with poorer RFS (p < 0.0001).

- When considering the mutations identified as not being prognostic within the discovery cohort, FLT3-TKD was predictive of higher relapse (p = 0.005), and inferior OS (p = 0.019) and RFS rates (p = 0.0005).

- Neither IDH1 nor IDH2 mutations were associated with relapse risk.

Impact of pretransplant conditioning

Within the combined cohorts, patients who received MAC experienced fewer relapses and superior OS compared with those who received reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) (p < 0.0001 for both). This was also consistent in patients <60 years old (p < 0.0001 for both).

Melphalan-based RIC regimens were associated with improved relapse rates compared to MAC regimens, and other RIC regimens, across patients who were MRD-negative (p = 0.009) and MRD-positive (p = 0.003). Compared solely to other RIC regimens, the addition of melphalan improved relapse rates in those who were MRD-negative (p = 0.015) and MRD-positive (p = 0.002). This translated to a survival benefit in patients who were MRD-positive (p = 0.012), but not in those who were MRD-negative (p = 0.37).

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors

Multivariate analysis identified the presence of MRD (FLT3-ITD+ or NPM1+ AML) as an important factor associated with increased risk of relapse, in addition to the treatment with non-melphalan RIC. However, a favorable European LeukemiaNet risk score was associated with a reduced risk of relapse (Table 2).

Table 2. Multivariate analysis of factors associated with OS in the combined cohort*

|

CI, confidence interval; ELN, European LeukemiaNet; HR, hazard ratio; MRD, measurable residual disease; OS, overall survival; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning. |

||

|

Factor |

HR (95% CI) |

p value |

|---|---|---|

|

MRD |

||

|

FLT3-ITD+ |

2.938 (2.152–4.011) |

<0.0001 |

|

NPM1+ AML |

3.032 (2.169–4.238) |

<0.0001 |

|

Conditioning regimen |

||

|

RIC with melphalan |

0.932 (0.68–1.277) |

0.661 |

|

RIC other |

1.743 (1.355–2.243) |

<0.0001 |

|

ELN risk group |

||

|

Favorable |

0.612 (0.434–0.864) |

0.005 |

|

Intermediate |

0.905 (0.701–1.169) |

0.445 |

Conclusion

The pre-MEASURE study is the largest dataset of NGS-MRD reported to date, in which the clinical use of NGS-MRD was validated using the NPM1 and FLT3-ITD mutations in patients in CR1 prior to allo-HSCT. The high rate of patients in CR1 with NPM1 and FLT3-ITD positivity (therefore, patients at a high risk of relapse) who proceeded to transplant, was highlighted. Specific mutations for MRD-targeting were identified, and the survival benefit provided by melphalan in the RIC conditioning regimens was demonstrated, particularly for MRD-positive patients.

The AML Hub spoke with Christopher Hourigan about the results from the pre-MEASURE trial. You can watch the video below.

Can pre-transplant MRD testing predict patients who are more likely to relapse?

Your opinion matters

In AML, at what stage is an MRD result most informative?

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Christopher Hourigan

Christopher Hourigan