All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know AML.

The aml Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the aml Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The aml and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The AML Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Syndax, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kura Oncology, AbbVie, and has been supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group.

Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View AML content recommended for you

Novel induction approaches with gemtuzumab ozogamicin for de novo AML

Innovative induction regimens, either with new combinations of well-established drugs or recently approved agents, or novel treatment schedules, are currently under investigation to improve outcomes for the treatment of de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO), when added to intensive chemotherapy, has been associated with improved outcomes in this patient population; however, the best use of GO in induction therapy remains unclear.1

During the 63rd American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting and Exposition, investigators presented findings from two studies investigating whether GO would improve event-free survival (EFS) when used in combination with cladribine, high-dose cytarabine, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and mitoxantrone (CLAG-M)1 or added to cytarabine instead of idarubicin2 here, we summarize key results.

GO combined with CLAG-M1

- This was a single-arm, single-center, phase I/II dose escalation study (NCT03531918).

- Primary objectives for phase I were to determine maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and recommended phase II dose (RP2D), and for phase II was to evaluate the 6-month and 1-year EFS rate.

- Inclusion criteria for patients were: ≥18 years of age; untreated non-acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) AML or other high-grade myeloid neoplasm (defined as ≥10% blasts in marrow or blood); treatment-mortality score ≤13.1; and adequate organ function.

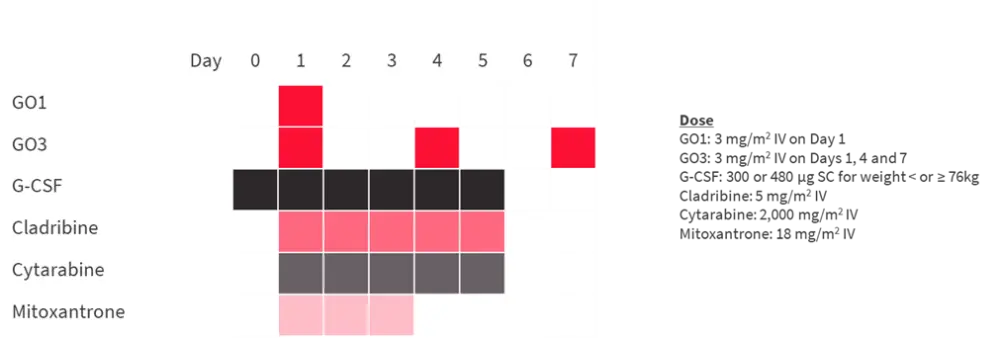

- GO 3 mg/m2 IV was added to CLAG-M on Day 1 (GO1) or Days 1, 4, and 7 (GO3) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study design*

G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; GO, gemtuzumab ozogamycin; IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous.

*Adapted from Godwin et al.1

Results

Total number of patients was 66 with a median age of 65 years (range, 19–80). The majority of patients had AML (80%) and 42% of patients had a secondary disease. Eighteen patients were treated in phase I cohort and 60 patients were included in the RP2D cohort (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient characteristics*

|

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; MDS-EB2, myelodysplastic syndromes with excess blasts 2; RP2D, recommended phase 2 dose; TRM, treatment-related mortality. |

||

|

Characteristic, % |

Phase I cohort |

RP2D cohort |

|---|---|---|

|

Median age, years (range) |

66 (29–78) |

65 (19–80) |

|

Diagnosis |

||

|

AML |

78 |

80 |

|

MDS-EB2 |

22 |

12 |

|

Other |

0 |

8 |

|

Secondary disease |

44 |

42 |

|

Risk category |

||

|

Favorable |

39 |

35 |

|

Intermediate |

28 |

20 |

|

Adverse |

33 |

45 |

|

TRM score, median (range) |

3.9 (0.14–10.4) |

3.5 (0.02–11.8) |

Phase I results yielded a RP2D of 3 mg/m2 GO given on Days 1, 4, and 7; AEs recorded in this cohort appeared to be similar to those seen with CLAG-M alone. Dose-limiting toxicities included Grade 3 left ventricular dysfunction, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, intracranial hemorrhage, and Grade 4 aminotransferase level increase.

Outcomes from phase II cohort are summarized below:

- Overall response rate was 87% with a complete remission (CR) rate of 77%.

- 88% of remissions had minimal residual disease negativity.

- 5% of patients had resistant disease.

- No deaths occurred within 8 weeks of treatment.

- Patients with favorable-risk disease had low incidence of relapse and high event-free overall survival (OS).

A validation cohort of 174 patients who were treated with CLAG-M was used to compare results with CLAG-M plus GO.

- Even though the combination with GO seemed to be associated with more favorable response rates, there was no statistically significant differences.

- 8-week mortality (p = 0.014) was significantly lower with the GO combination; however, time to neutrophil (p = 0.001) and platelet recovery (p < 0.001) were significantly longer.

- Time to relapse, and EFS estimates were similar in the overall study population; there was a statistically significant benefit in OS with the GO combination (p = 0.048)

- The benefit of GO was more apparent in different risk groups.

- GO was associated with significantly longer EFS in favorable-risk settings (p = 0.01) and there was a borderline significant longer time to relapse and OS (p = 0.05).

- The difference in OS in favorable- and intermediate-risk settings was borderline significant (p = 0.05 for both), which was not the case for adverse-risk disease.

This study suggested that adding fractionated doses of GO to CLAG-M chemotherapy may be a safe option with promising anti-leukemic activity for adult patients with newly diagnosed AML or other high-grade myeloid neoplasm. The benefit appeared to be greater in patients with favorable-risk disease when compared to CLAG alone. Time to platelet and neutrophil recovery was delayed when GO was added.

Replacing idarubicin by GO: ALFA1401 – Mylofrance 4 study2

- This was a randomized (2:1), multi-center, prospective phase II study (NCT02473146) enrolling patients aged 60–80 years, with untreated de novo AML and favorable or intermediate cytogenetic risk.

- Patients with unfavorable or irrelevant cytogenetics were excluded from the analysis.

- Primary endpoint was EFS, defined as primary refractory disease, relapse, or death. Secondary endpoints included response rate, cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR), overall survival (OS), incidence of early death, Grade 3–5 adverse events (AEs) or serious AEs (SAEs).

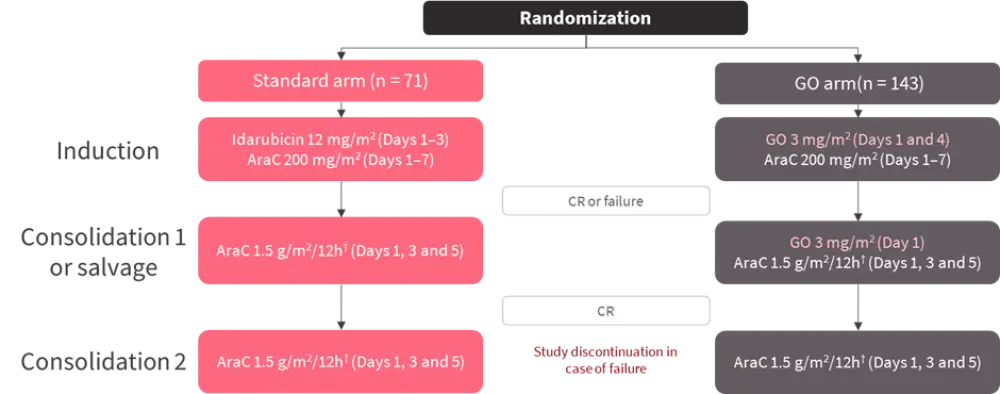

- Standard treatment arm consisted of idarubicin and cytarabine, and experimental arm (GO arm) replaced idarubicin by GO (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Study design*

AraC, cytosine arabinoside; CR, complete remission; GO, gemtuzumab ozogamicin; h, hours.

*Adapted from Lambert et al.2

†Patients over 70 years of age, AraC dose was 1 g/m2/12h

The total number of patients included in the analysis was 214 (Table 2).

Table 2. Patient characteristics*

|

GO, gemtuzumab ozogamicin; IQR, interquartile range; WBC, white blood cell. |

||

|

Characteristic, % |

Standard arm |

GO arm |

|---|---|---|

|

Male sex |

48 |

62 |

|

Median age, years (IQR) |

69 (62–79) |

70.5 (61–80) |

|

Median WBC, × 109/L (IQR) |

5.8 (0.4–275.4) |

3.8 (0.5–241.5) |

|

Intermediate-risk cytogenetics |

94 |

93 |

|

NPM1 mutation |

35 |

26 |

|

FLT3-ITD mutation |

17 |

15 |

Results

- The study failed to meet its primary endpoint as the median EFS was not significantly different in both arms (standard arm: 15.2 months vs GO arm: 12.4 months; p = 0.067).

- Interestingly, gender was found to have an impact on EFS (p = 0.0017); GO led to poor outcomes in women even after adjustment for known prognostic factors.

- There was no significant difference in composite response rates between both arms (standard arm: 90% vs GO arm: 82%; p = 0.73).

- Complete remission (CR) was 72% and 68%, respectively.

- Primary refractory disease occurred in 6% and 11% of patients, respectively.

- Death rate was 4% and 8%, respectively.

- The number of patients who underwent transplantation were higher in the standard arm (30%) vs GO arm (12%).

- 2-year CIR did not show any significant difference between arms (standard arm: 48% vs GO arm: 61%; p = 0.11).

- Overall, 122 patients died with no significant difference in median OS (standard arm: 36.5 months vs GO arm: 25.5 months; p = 0.23).

- Safety analysis revealed that:

- The number of patients experiencing ≥1 SAEs was significantly greater in the GO arm (48%) vs standard arm (35%); p = 0.041.

- There was no significant difference in early death rate (<60 days), and the number of patients with one or more Grade 3–5 AEs.

- Grade 3–5 AEs included infection, cardiac disorder, hemorrhages, persistent thrombocytopenia, veno-occlusive disease.

In conclusion, this study failed to demonstrate an additional benefit of GO over idarubicin as a frontline therapy for older patients with de novo AML. In terms of safety, GO was associated with more SAEs compared with standard therapy which may limit the transplant indication in patients.

Additional content

Watch this video with Amir Fathi where he talks about the potential impact of new immunotherapy modalities in AML, here.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content