All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know AML.

The aml Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the aml Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The aml and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The AML Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Syndax, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kura Oncology, AbbVie, and has been supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group.

Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View AML content recommended for you

Impact of allo-HSCT and Fried’s frailty phenotype in older patients with AML

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is a potentially curative treatment in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), depending on the availability of a suitable donor.1 While allo-HSCT has been shown to improve survival outcomes in patients aged <60 years with higher-risk AML, the overall outcomes among older patients with AML remain poor; therefore, further information is needed on the benefits of allo-HSCT in older and/or frail patients.1 Older age correlates to an increased comorbidity burden and, while the impact of comorbidities on the benefits of allo-HSCT has not yet been determined, there remains an unmet need in this population.1

Here, we summarize an observational study published in Blood by Sorror et al.,1 assessing the benefits of allo-HSCT in older patients with AML, and a presentation by McCurdy,2 evaluating the impact of Fried’s frailty phenotype (FFP) on survival outcomes post-allo-HSCT in older patients with AML or myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), presented during the 2023 Transplantation & Cellular Therapy Meetings of the ASTCT and CIMBTR.

An 8-year pragmatic observation evaluation of the benefits of allogeneic HCT in older and medically infirm patients with AML1

Study design

This multicenter, prospective, observational study (NCT01929408) enrolled patients across 13 U.S. centers between July 2013 and December 2017. Eligible patients were aged 18–80 years, had newly diagnosed AML, relapsed/refractory AML, or high-risk MDS, and were treated with AML-like therapy at either lower or higher intensity. Patients with a predicted overall survival (OS) of <6 months or those receiving only palliative/supportive care were excluded.

The primary endpoint was OS and secondary endpoints included quality of life (QoL), functional status, and frailty.

Patient characteristics

In total, data from 692 patients were analyzed with 45.5% having received allo-HSCT, 76.5% of which received allo-HSCT in first complete remission (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics*

|

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CR, complete remission, ELN, European LeukemiaNet; HSCT-CI, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation-comorbidity index; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; R/R, relapsed/refractory. |

|

|

Characteristics, % (unless stated otherwise) |

All patients |

|---|---|

|

Age, years |

|

|

18–49 |

22 |

|

50–59 |

21 |

|

60–64 |

14 |

|

54–69 |

19 |

|

10–74 |

14 |

|

75–79 |

9 |

|

≥80 |

1 |

|

Augmented HSCT-CI |

|

|

0–1 |

15 |

|

2–3 |

29 |

|

4–5 |

23 |

|

≥6 |

33 |

|

2017 ELN risk classification |

|

|

Favorable |

21 |

|

Intermediate |

43 |

|

Adverse |

36 |

|

KPS |

|

|

>70 |

83 |

|

≤70 |

17 |

|

AML composite model |

|

|

0–3 |

13 |

|

4–6 |

32 |

|

7–9 |

32 |

|

≥10 |

23 |

|

Diagnosis |

|

|

Newly diagnosed AML |

77 |

|

R/R AML |

14 |

|

High-risk MDS |

9 |

|

Status posttreatment |

|

|

Never achieved CR |

44 |

|

Achieved CR |

56 |

Results

The median follow-up among surviving patients was 53.6 months (range, 1.1–88.5 months). At enrollment, most patients’ main treatment goal was cure (80%), followed by QoL (36%), and length of life (33%). Re-assessment at 3 or 6 months after enrollment in the non-allo-HSCT group, and at the closest time point before receiving allo-HSCT in the allo-HSCT group, showed that cure remained the main treatment goal in both groups (74% and 87%, respectively) followed by QoL (51% and 44%, respectively). There was a clear difference in patient and physician perception of the chance of a cure, with 65% of patients estimating they had a >75% chance, whereas physicians estimated 7% of patients had a >75% chance. Physicians generally estimated a higher chance of cure for patients in the allo-HSCT group (6% estimated >75% chance of cure, 78% estimated a 25–74% chance of cure) compared with patients in the non-allo-HSCT group (7% estimated >75% chance of cure, 47% estimated 25–74% chance of cure).

Multivariable analysis revealed that increasing age, comorbidity index scores, intermediate and adverse European LeukemiaNet (ELN) risk, AML type at enrolment, response to treatment, frailty, impaired QoL, increased depressive symptoms, and dependent status were significantly associated with mortality (Table 2).

Table 2. Multivariable analysis of risk factors associated with mortality*

|

4-MWT, National Institutes of Health Toolbox 4-Meter Walk Gait Speed Test; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CI, confidence interval; CR1, first complete remission; CR2, second complete remission; CR3, third complete remission; ELN, European LeukemiaNet; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; HSCT-CI, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation comorbidity index; HR, hazard ratio; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; QoL, quality of life; R/R, relapsed/refractory. |

||

|

Risk factor |

HR (95% CI)† |

p value |

|---|---|---|

|

Augmented HSCT-CI |

|

|

|

0–1 |

1.0 |

— |

|

2–3 |

1.79 (1.05–3.06) |

0.03 |

|

4–5 |

2.42 (1.44–4.07) |

0.0009 |

|

≥6 |

3.69 (2.24–6.06) |

<0.0001 |

|

Age, years |

||

|

0–59 |

1.0 |

— |

|

60–64 |

1.50 (1.05–2.13) |

0.02 |

|

65–69 |

1.36 (0.99–1.86) |

0.06 |

|

≥70 |

2.19 (1.65–2.91) |

<0.0001 |

|

ELN cytogenetic risk‡ |

||

|

Low |

1.0 |

— |

|

Intermediate |

1.53 (1.03–2.28) |

0.03 |

|

Adverse |

2.35 (1.56–3.54) |

<0.0001 |

|

Status at enrollment |

||

|

Newly diagnosed AML |

1.0 |

— |

|

R/R AML |

1.65 (1.24–2.20) |

0.0005 |

|

Status after treatment |

||

|

Never reached CR |

1.0 |

— |

|

CR1 |

0.29 (0.23–0.37) |

<0.0001 |

|

Relapsed after CR1 |

1.66 (1.24–2.23) |

0.0007 |

|

CR2 |

0.78 (0.44–1.37) |

0.38 |

|

Relapsed after CR2 |

3.41 (1.81–6.44) |

0.0002 |

|

CR3 |

3.80 (1.19–12.07) |

0.02 |

|

FACT-G (per 10 points)§ |

0.89 (0.81–0.98) |

0.02 |

|

PHQ-9 depressive symptoms¶ |

1.03 (1.00–1.06) |

0.03 |

|

ADL# |

0.95 (0.90–1.00) |

0.05 |

|

4-MWT mean time** |

1.31 (1.09–1.57) |

0.004 |

The estimated 4-year OS for patients who underwent allo-HSCT was 54%. The unadjusted analysis revealed a 29% reduction in risk of mortality in patients receiving allo-HSCT versus those not receiving allo-HSCT. Allo-HSCT versus no allo-HSCT was associated with a 37%, 45%, and 63% reduction in risk of mortality in patients with augmented hematopoietic stem cell transplantation comorbidity index (HSCT-CI) scores ≥4 (p = 0.0004), ELN intermediate risk (p = 0.0004), and ELN adverse risk (p < 0.0001), respectively. However, after adjusting for variables associated with mortality, allo-HSCT was only associated with improved OS in patients with an adverse ELN risk (p = 0.01) and in patients who had never achieved first complete remission (p = 0.02; Table 3).

Table 3. Unadjusted and adjusted analysis of the association of allo-HSCT with mortality*

|

4-MWT, National Institutes of Health Toolbox 4-Meter Walk Gait Speed Test; ADL, activities of daily living; CI, confidence interval; CR, complete remission, ELN, European LeukemiaNet; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; HSCT-CI, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation comorbidity index; HR, hazard ratio; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Score; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9. †Adjusted for the augmented HSCT-CI, age, ELN cytogenetic risk, relapsed/refractory AML at enrollment, posttreatment CR1 status, treatment intensity, sum PHQ-9, KPS, ADL, FACT-G, and 4-MWT (posttreatment CR1 status, sum PHQ-9, KPS, ADL, FACT-G, and 4-MWT modeled as time-dependent variables, with missing indicator to account for those without data). |

|||||

|

Risk factors |

n |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted† |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HR (95% CI) |

p value |

HR (95% CI) |

p value |

||

|

All patients |

692 |

0.71 (0.57–0.88) |

0.002 |

0.85 (0.66–1.09) |

0.19 |

|

Aged ≥65 years |

295 |

0.65 (0.46–0.90) |

0.01 |

0.79 (0.53–1.16) |

0.22 |

|

Augmented HSCT-CI scores ≥4 |

353 |

0.63 (0.46–0.86) |

0.0004 |

0.84 (0.58–1.21) |

0.34 |

|

ELN intermediate risk |

296 |

0.55 (0.40–0.77) |

0.0004 |

0.81 (0.55–1.17) |

0.26 |

|

ELN adverse risk |

248 |

0.37 (0.25–0.54) |

<0.0001 |

0.58 (0.38–0.89) |

0.01 |

|

Achieved CR1 |

510 |

0.85 (0.67–1.09) |

0.20 |

0.96 (0.72–1.27) |

0.75 |

|

Not achieved CR1 |

182 |

0.27 (0.15–0.51) |

<0.0001 |

0.45 (0.22–0.90) |

0.02 |

Adjusted analysis showed no significant differences between the pre- and post-allo-HSCT groups in terms of Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General, European Quality of Life 5-dimensions, Patient Health Questionnaire 9, Fried’s Frailty Index, National Institutes of Health Toolbox 4-Meter Walk Gait Speed Test, or instrumental activities of daily living scores. The pre-allo-HSCT versus non-allo-HSCT group showed a higher social activity log (p < 0.001), ENRICHD social support instrument (p = 0.003), activities of daily living (p = 0.004) scores, and performance status (p < 0.001). With regard to changes over time, no differences were seen in QoL, functional status, or frailty in post- or non-allo-HSCT groups.

Frailty phenotype declines in older patients after allogeneic transplantation and predicts subsequent overall survival2

Study design

This prospective study enrolled 78 patients aged ≥60 years with AML or MDS who were eligible for allo-HSCT. The FFP was measured at five time points: pre-allo-HSCT and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-allo-HSCT.

The primary endpoint was conditional survival (CS) measured by FFP.

- FFP at 3 months was used to estimate the 12-month CS rates (15-month OS)

- FFP at 6 months was used to estimate 12-month CS rates (18-month OS)

Patient characteristics

In total, 78 patients were enrolled, with 24, 49, and 5 patients classed as fit, pre-frail, and frail, respectively. According to the Disease Risk Index, 80% of patients were grouped as intermediate-risk, with the remaining 19% at high/very-high risk. In total, 41% of patients had a Karnofsky Performance Status <90, while 13.1%, 59%, and 28% of patients had a HSCT-CI of 0, 1–2, and ≥3, respectively.

Patients with the frail phenotype had a higher median age of 73 (range, 67–75 years; p = 0.01) versus 67 years in pre-frail (range, 60–78 years) and 65 years in fit patients (range, 61–73 years). Patients who were frail had a higher median HSCT-CI of 5 (range 3–9) compared with patients who were pre-frail (median, 3; range 0–7) and patients who were fit (median, 2.5; range 0–9; p = 0.04). The median follow-up was 31 months.

Results

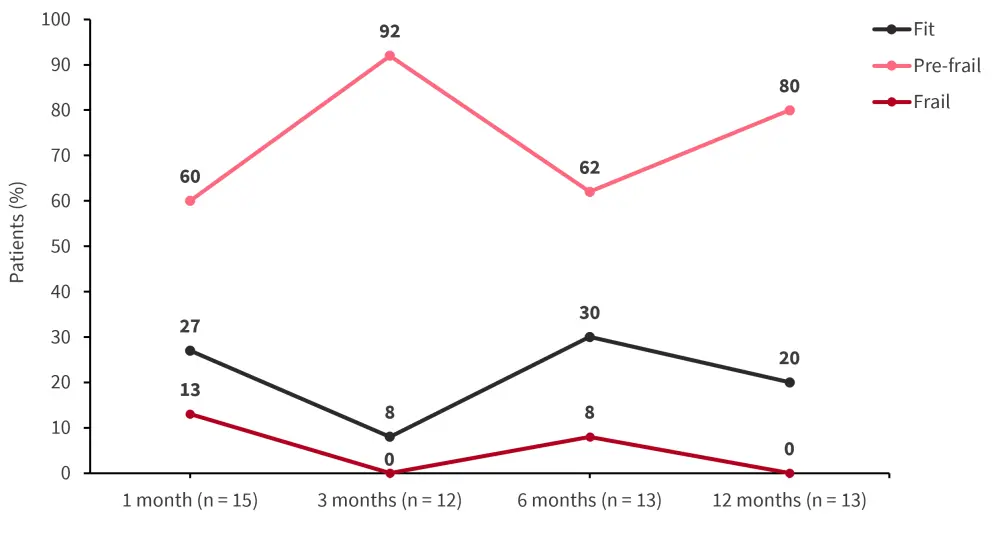

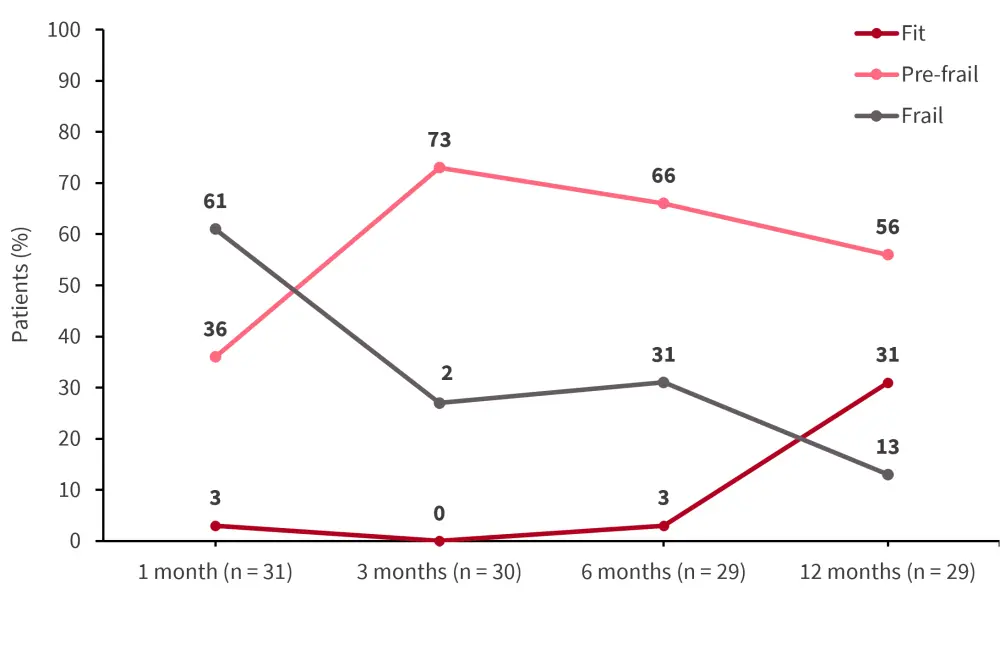

Overall, 65% of patients experienced a decline in fitness post-HSCT. The mean FFP declined over time reaching frail status at 6 months in patients who died within the first year. However, mean FFP stabilized at 3–6 months and improved at 12 months in patients who survived (Figure 1, Figure 2). The 1- and 2-year OS rate was 74% and 58% for the overall population, respectively. Using 6-month frailty status, patients who were pre-frail showed an improved 18-month OS rate compared with patients who were frail (92% vs 50%; p = 0.005).

Figure 1. FFP measured over time post-allo-HSCT in the fit pre-allo-HSCT group (n = 24)*

Allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; FFP, Fried’s frailty phenotype.

*Data from McCurdy.2

Figure 2. FFP measured over time post-allo-HSCT in the pre-frail pre-allo-HSCT group (n = 49)*

Allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; FFP, Fried’s frailty phenotype.

*Data from McCurdy.2

Conclusion

The study by Sorror et al.1 demonstrated that, while allo-HSCT conferred a survival benefit over no allo-HSCT in the unadjusted model, this benefit was restricted to patients with ELN adverse risk and patients who did not achieve complete remission in the multivariate analysis. While this study is limited by its observational nature, these results warrant further investigation in randomized controlled clinical trials. This study highlights the importance of patient selection for allo-HSCT. In the study by McCurdy,2 it was highlighted that functional assessment of FFP should be performed before and after allo-HSCT to assist with the risk stratification of patients. Future studies may look at improving patient fitness pre- and post-allo-HSCT, which could improve survival outcomes.

Overall, while allo-HSCT is recognized as a potentially curative therapy for patients with AML, there is a lack of randomized controlled trials assessing the efficacy of allo-HSCT versus alternative therapies in older, frailer populations; the optimal selection of patients for allo-HSCT represents an unmet need warranting further investigation.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content