All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit Know AML.

The aml Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the aml Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The aml and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The AML Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Syndax, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kura Oncology, AbbVie, and has been supported through an educational grant from the Hippocrate Conference Institute, an association of the Servier Group.

Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View AML content recommended for you

Clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and outcomes in secondary AML: A large scale registry study

Secondary acute myeloid leukemia (sAML) accounts for 18–28% of total AML cases and is associated with poor overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS). There are many treatment strategies for sAML; however, hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is the only curative option. Furthermore, clarity is needed as to whether sAML should be considered an independent prognostic factor. Data have shown that patients diagnosed with sAML are usually of older age, and frequently present with comorbidities, which may influence the poor survival outcomes in this population.

A registry study published by Martínez-Cuadrón et al.1 in Blood Advances analyzed the clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and outcomes of >2,000 patients diagnosed with sAML and compared these data with patients diagnosed with de novo AML. We summarize the key results from these analyses below.

Study design

A registry study (NCT02607059) analyzing adult patients in Spanish and Portuguese institutions between 1990–2019 reported to the multinational PETHEMA AML registry.

Figure 1. Study design*

3+7, idarubicin or daunorubicin and Ara-C; AZA, azacitidine; CR, complete remission; CRi, complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery; DEC, decitabine; EFS, event-free survival; FLAG-Ida, fludarabine, idarubicin and Ara-C; FLAGIDA-Lite, fludarabine, Ara-C and idarubicin; FLAT, fludarabine, Ara-C and topotecan; FLUGA, fludarabine and Ara-C; ICE, idarubicin, Ara-C, and etoposide; LDAC, low-dose cytarabine; OS, overall survival; sAML, secondary acute myeloid leukemia.

*Adapted from Martínez-Cuadrón et al.1

Results

Baseline characteristics

Patients with sAML included those with:

- AML derived from myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS-AML; 44%, n = 884)

- AML derived from myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDS/MPN-AML; 10%, n = 209)

- AML derived from MPN (MPN-AML; 11%, n = 226)

- antecedent neoplasia without prior chemotherapy/radiotherapy (neo-AML; 9%, n = 179)

- therapy-related AML (t-AML; 25%, n = 502)

Compared to patients with de novo AML (Table 1), patients with sAML:

- had increased incidence for adverse characteristics, including older age

- were more often male

- more frequently presented with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) ≥2

- had lower median white blood cell (WBC) count and fewer blast cells in bone marrow (BM)

- more often had high-risk cytogenetics

- had fewer favorable prognostic FLT3-ITD and NPM1 mutations

Table 1. Comparison of characteristics between patients with de novo and sAML*

|

BM, bone marrow; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ITD, internal tandem duplication; PB, peripheral blood; sAML, secondary acute myeloid leukemia; WBC, white blood cell. |

|||||

|

Characteristic |

de novo AML |

sAML |

p value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Median age, years (range) |

64 (18–99) |

n = 6,201 |

69 (18–104) |

n = 2,306 |

< 0.001 |

|

Male, % |

53 |

n = 6,127 |

60 |

n = 2,304 |

< 0.001 |

|

ECOG PS ≥2, % |

28 |

n = 4,819 |

35 |

n = 1,821 |

< 0.001 |

|

Median WBC in PB (range) |

10.4 × 109/L |

n = 5,762 |

6.6 × 109/L |

n = 2,039 |

< 0.001 |

|

Median % blast cells in BM (range) |

64 (0–100) |

n = 4,937 |

42 (0–100) |

n = 1,675 |

< 0.001 |

|

Adverse cytogenetic risk, % |

24 |

n = 4,501 |

40 |

n = 1,598 |

< 0.001 |

|

FLT3-ITD-positive, % |

21 |

n = 3,301 |

11 |

n = 990 |

< 0.001 |

|

NPM1-positive, % |

33 |

n = 3,097 |

16 |

n = 927 |

< 0.001 |

In terms of treatment (n = 2,310), the majority of patients with sAML received intensive chemotherapy (IC) (38%), 24% received best supportive care, 14% hypomethylating agents, 14% non-IC, and 3% were treated within a clinical trial setting.

Patients who received best supportive care were older and had poorer ECOG scores, higher uric acid, lactate dehydrogenase, creatinine, and alkaline phosphatase serum levels, lower albumin levels, and higher WBC in peripheral blood and BM blast percentage. In contrast, patients treated with IC were younger, more frequently diagnosed with t-AML or neo-AML, had higher BM blast cells percentage, more favorable cytogenetics, and more frequently carried favorable NPM1 mutations.

Regarding characteristics of patients with sAML:

- patients with MDS-AML and t-AML had better ECOG scores

- patients with MDS/MPN-AML had higher WBC counts

- patients with t-AML and neo-AML had a higher BM blast percentage and more frequent favorable cytogenetics, NPM1, and FLT3-ITD mutations

CR/CRi

Of the 1,486 patients with sAML with available data, 41% achieved complete remission (CR) or complete remission with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi), 8% reached partial remission (PR), while 38% were resistant to treatment, and 13% died during frontline treatment. Furthermore, 35% of patients who achieved CR/CRi had previously received HSCT, which was autologous in 51 (9%) patients and allogeneic in 152 (26%).

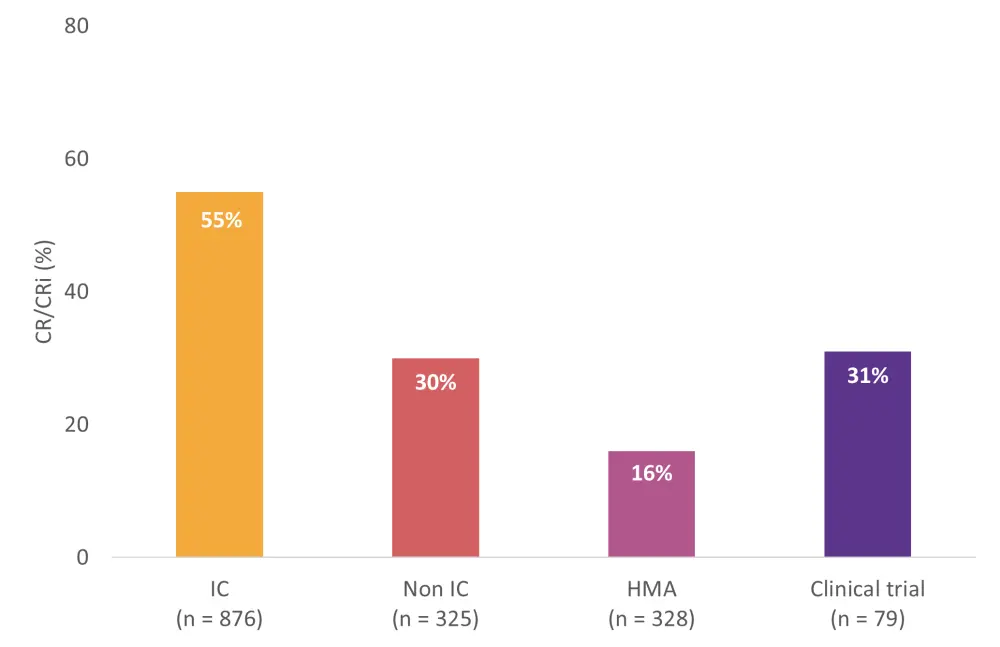

- Frontline IC was associated with the highest CR/CRi rate (Figure 4)

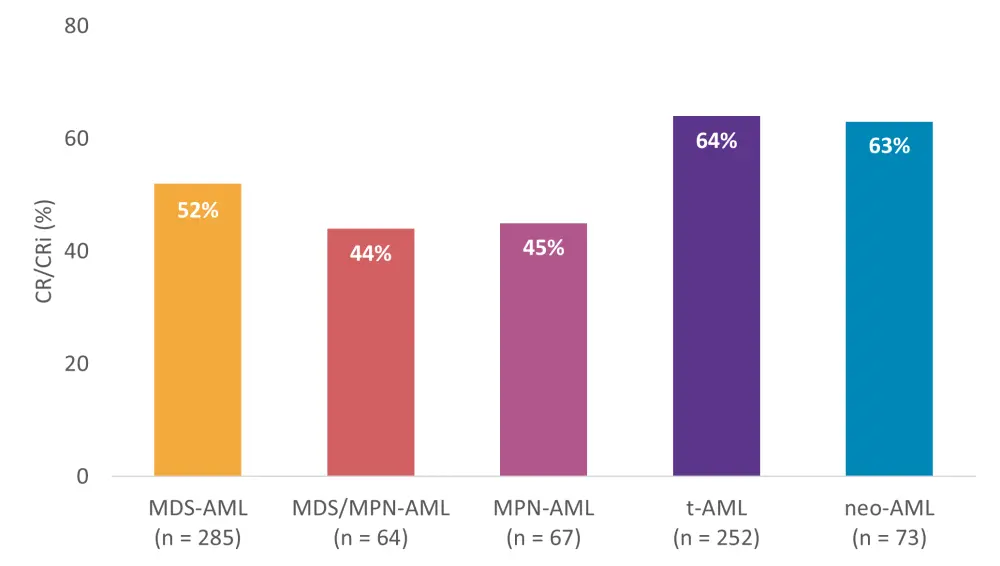

- Within patients who received IC, those with t-AML and neo-AML had the highest CR/CRI rates (Figure 5)

-

Figure 1. CR/CRi rate according to frontline treatment given*

CR, complete remission; CRi, complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery; HMA, hypomethylating agents; IC, intensive chemotherapy; Non-IC, non-intensive chemotherapy.

*Adapted from Martínez-Cuadrón et al.1

Figure 1. CR/CRi according to type of sAML in patients receiving IC*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CR, complete remission; CRi, complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery; IC, intensive chemotherapy; MDS-AML, AML derived from myelodysplastic syndromes; MDS/MPN-AML, AML derived from myelodysplastic syndromes/myeloproliferative neoplasms; neo-AML, AML with antecedent neoplasia without prior chemotherapy/radiotherapy; s-AML, secondary AML; t-AML, therapy-related AML.

*Adapted from Martínez-Cuadrón et al.1

In multivariate analyses, sAML diagnosis (p < 0.001), age (p < 0.001), ECOG PS (p < 0.001), WBC count (p < 0.001), and creatinine level >1.2 mg/dL (p = 0.003) were independent adverse prognostic factors for CR/CRi; while presence of NPM1 mutation, and favorable and intermediate cytogenetic risk were favorable prognostic factors (p < 0.001). Among patients with sAML, independent unfavorable prognostic factors for CR/CRi included age, ECOG PS, WBC count, and bilirubin levels >1.2 mg/dL. Favorable prognostic factors were NPM1 mutation, favorable and intermediate risk cytogenetics, and a diagnosis of t-AML or neo-AML.

Overall survival

For the entire cohort (N = 8,521), median OS was 9.1 months (95% CI, 8.7–9.6 months)

- Median OS was lower in patients with sAML compared with de novo AML (5.6 months [95% CI, 5.2–6.3] vs 10.9 months [95% CI, 10.3–11.5]; p < 0.001).

- 1- and 5-year OS rates were both lower in patients with sAML vs de novo AML (1-year, 31.4% vs 47.8%; 5-year, 8.3 vs 23.4%; p < 0.001 for both).

- Patients who received IC or HMAs had a greater median OS than with other treatments (9.9 months [95% CI, 8.9–11.4] and 9.0 months [95% CI, 7.6–10.6], respectively).

- Median OS was significantly lower in patients with sAML originating from previous hematologic disorders (5.3 months; 95% CI, 5.0–6.1) compared to those with neo-AML (6.1 months; 95% CI, 5.1–7.8) or t-AML (5.7 months; 95% CI, 4.1–7.8; p = 0.04).

- Although survival was improved in patients with neo-AML in comparison to patients with other types of sAML following IC, no significant difference was observed between patients with de novo AML (17.2 months; 95% CI, 16.0–18.6) and neo-AML (14.6 months; 95% CI, 10.3–42.4; p = 0.63).

Following multivariate analysis, unfavorable prognostic factors for OS included ECOG PS ≥2, WBC count ≥10 × 109/L, BM blast cells >70%, creatinine >1.3 mg/dL, and alkaline phosphatase >150 U/L. Favorable prognostic factors included age of 30–59, diagnosis of neo-AML, platelet count >20 × 109/L, albumin >3.5 g/dL, favorable and intermediate cytogenetic risk, and presence of favorable NPM1 mutation.

When considering the entire study cohort including patients with de novo AML, sAML was identified as an independent prognostic factor (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02–1.15; p = 0.01). With neo-AML excluded, sAML was a significant predictor of OS (HR 1.09; 95% CI, 1.02–1.16; p = 0.008).

Event-free survival

The median EFS in patients with sAML was 3.6 months (n = 1,394), with a 1- and 5-year EFS of 22.2% and 8.4%, respectively. Frontline treatment with IC (4.1 months), HMA (4.8 months), or as part of a clinical trial (3.3 months) were associated with higher median EFS compared to non-IC (1.7 months; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

This large-scale registry study confirmed increased incidence of adverse characteristics, such as older age, ECOG PS, and unfavorable karyotype in patients with sAML. Additionally, multivariate analysis confirmed that sAML was an independent prognostic factor for CR/CRi and OS. Survival outcomes varied depending on the type of sAML and treatment, with patients receiving HSCT and IC having superior remission and survival rates. Furthermore, patients with neo-AML had similar survival rates to those with de novo AML. The authors concluded that, given the high number of patients either ineligible for these treatments or diagnosed with AML transformed from myeloproliferative or myelodysplastic disorders, the development of more effective therapeutic strategies for this vulnerable population should be a high priority.

Limitations of this study highlighted by the authors were that registry data did not include the majority of patients with AML in Spain and Portugal, molecular data was not analyzed, the majority of sAML cases included were after 2010, and some variables had a proportion of missing data that meant granular analysis was not possible.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content